Five Poems

9:40 a.m. / Venipuncture

The way they step on one another’s heels

until a spindle-legged woman with dyed

hair trips in the queue, and all stick

their necks forward for fear someone

might overtake them on the production

line behind the door they all strive to get

to, and on which three lab nurses

squat like giant mosquitoes, sucking

blood from seven in the morning, it’s now

getting on to ten and no one knows yet

what is to come, if this will be enough

or they will be ushered into an inner

room from where further doors open.

Outside, throbbing fall holds out

its rich grapes. The sun glows

relentlessly on the translucent berries.

Metamorphoses

You start awake in the middle of the night

to glimpse by your head, lying on the white

bedsheet, an unstirring, black vermin,

it’s watching you. You sweep it off with the pillow

and look for it on the floor, hoping it was

a stag beetle. Seeing the light on, the one you love

comes in: Anything wrong? he asks.

Now you can tell you had imagined the scene, only

because you don’t shrink as you normally would,

had you not dreamt it. No, nothing, you answer.

While knowing something’s wrong. The one who lay on your

pillow a while ago is now watching you, black, unstirring.

The Place

The place, this cat, lives on. Indifferent

to our passing, it lies down on the windowsill,

giving us a cue: inside there are more rooms.

It looks out languidly and invites us in.

We were sitting on the green sofa. The Big Ben–like

tower music always reminded me of the death knell.

It would sound unexpectedly in the middle of conversation,

our time is up, the clock struck, it announced

and I would grab a parent’s hand and tug

at it: let’s go! Danger is lurking here.

On the wall my uncle of tragic fate

sat embracing his young wife

on a bough. How preposterous!

How could the slender girl in diaphanous

clothes and the serious-looking young man

sit embraced on a bough! Yet I clearly remember,

they sat there. The famous painter of the thirties

immortalized them. I don’t know where the crafty

device produced the music, if it was incorporated

in the back of the frame, or if there was

a wall clock nearby. And in the meantime

the grown-ups’ conversation, for instance:

“at the horrors her hair turned white overnight.”

They said it in a whisper so we wouldn’t hear, but we

caught it of course, munching our gingerbread.

My uncle’s family should have moved out of that

apartment. So, they all died before time.

I wanted to tell them in parting. But who

would listen to a twelve-year-old?

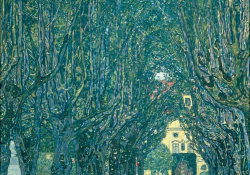

Beneath the tree in the picture the well-known figure,

the Reaper was seen: he was sawing (!) the tree.

I saw it all very clearly.

The Constancy of the Trojan Horse

The Trojan horse knocked on the door shyly

and came in with a clopping on the floor.

Hoof of a horse, I smiled to myself, then as I saw

the evergreen bouquet clumsily pressed

to his side, I chuckled inwardly:

gift of a stalking horse, and was amused by

my comparison. I offered him a seat,

disheartening him who, with a sideways

jerk of his head, gestured no,

to escape the pangs of sitting down.

There was a smell of freshly planed

wood. With a small sigh I thought of my

approaching birthday and looked out

for a last time at the world beyond

the window: church tower, rooftops,

short-flighted, sick pigeons.

As if about to start down the slope,

my visitor gave me an embarrassed

look, but soon an impatient snort

was to follow. I quickly realized:

this is the signal. From then on,

I remember exactly, I wished I could

stop my ears, not to hear the dreaded

wailing. The warriors might just as well

sleep on, or play cards in the horse’s

belly, no need to jump out with frightful

battle-cries, shaking their murderous

weapons at us. The trick works

every time. Here I sit with arms pressed

to my side, covering my face. And every time

they will slaughter me, and I am as surprised

as the first time it came to pass.

An Autobiography

When you start awake in the middle of the night,

unable to fall back asleep, you open

a book read umpteen times to find out

that the characters behave differently

and the plot takes another turn than you had

read, blindly, before. You idly gloss over

the description of lovers’ heart-rending good-byes

but the whip’s whizz on the twitching

hide of the jade unable to trudge

its load of coal echoes in your ear,

and you wail and weep like the impotent

elderly. Like your kin harnessed to the cart,

you scamper up and down, motionless.

Before your wide-open eyes fixed on the letters

the judgment of the axe suspended by a hair

takes shape: that you withheld the last drop

of water from the thirsting, although you knew the pain

of the cracked (mother)tongue; that you have lived

a stranger’s life instead of your own, and suchlike

charges. Like a newborn who would only

live for a few years, you cannot decide if

to get out of your swaddling-clothes and

shiver among the other outcasts.

Translations from the Hungarian

By Erika Mihálycsa

Editorial note: From Viszonyok könnye (1992), A letakart óra (2001), and A test imádása (2010).