What Working Behind the Scenes on Broadway Taught Me about Storytelling

I worked on the Broadway production of Jersey Boys for three years before I ventured up to the fly rail of the August Wilson Theater. It was pre-show and automation, lights, props, sound, and wardrobe were on the stage, thirty feet below. I watched them through the slatted floor as they ran their cues and set their props and costumes. Kenny, the fly man, had a lawn chair and a reading lamp up on the rail. Weighted ropes looped around pulley systems and dropped down to the floor of the stage. There were signatures across the brick walls. I searched for names I knew. I only had a few minutes up there and left before half hour, when the theater teemed with activity, but I thought about what the show looked like from the bird’s-eye view and how for most of the audience this would be the first and only time they’d see the performance, a special night. If we did our jobs right, they’d never wonder at the mechanics of the show. If we did our jobs right, they’d be immersed in the story.

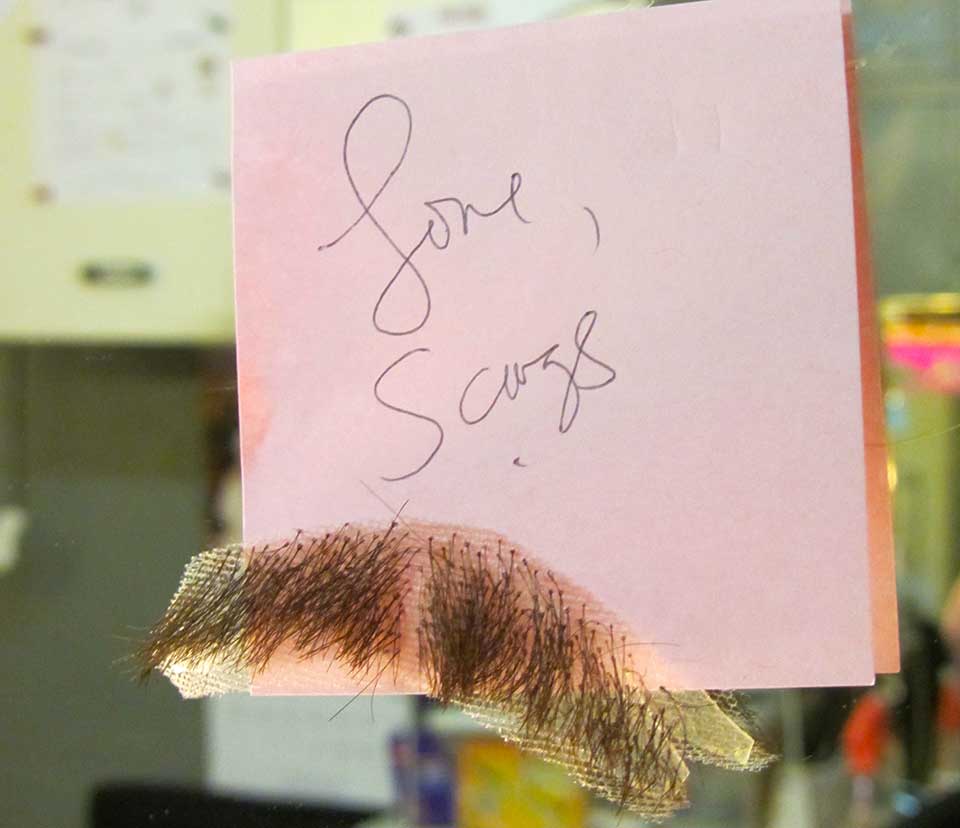

Below the stage was the theater basement, a gray, concrete expanse of space broken up by a loft and a lift, the sound desk, automation, the head electrician’s and carpenter’s offices, too. The musicians’ pit was in the basement, a rarity for Broadway shows, but there they were. And then there was the wardrobe department, a slip of a room crammed with sewing machines and costumes in need of repair. Adjacent to them was the hair department. That’s where I worked. My team and I were the wig masters, a silent and small niche of a job. We told ourselves that if the audience noticed the actors’ wigs, we’d failed. Two of the worst things that can happen to a wig person: 1. A wig falls off during a performance; 2. A reviewer mentions the wig in a review. As a department, we were lithe and sly, flexible, quick, and invisible.

We told ourselves that if the audience noticed the actors’ wigs, we’d failed.

For years, this was my bread-and-butter job. I was one of the last people the actors saw before they stepped on stage and one of the very few who lived in the wings, waiting for the wig changes as the show went on around us. Often, before the house was open, I walked across the stage and looked out into the empty audience. I didn’t picture the people who’d be sitting in the seats. Instead, I felt the energy building up beneath me. After the show, when the audience was gone and the ghost light lit for the theater ghosts so they could find their places on stage, it was the lingering energy dissolving into stillness that soothed me.

I struggled for a while to find meaning in all of it, the repetition, the invisibility, the yearning to be seen. But since the night on the fly rail when I looked down on the stage, not empty, but not yet ready to present the story, I’ve come to understand how existence itself is a group effort, mostly unseen; machinations behind the scenes play out on the stage we call our lives. Our roles are shockingly simple. We are a part of the story because we are storytellers. And we tell stories because we’re hardwired to do so. Stories measure the passage of time. Like clockwork, like a long-running Broadway show, they change incrementally. They seem like they’ll go on forever, but they always end.

I’ve come to understand how existence itself is a group effort.

The first day Jersey Boys moved into the August Wilson, the stage was at its emptiest. We had no idea if the show would be a flop or a hit or something in between. For all of us, it took a leap of faith and a willingness to go along for the ride. There were reminders of the fates of the shows that had come before: an unsmoked cigarette and a scene list from Little Shop of Horrors, a closing-night outfit from Little Women, an abandoned bouquet of flowers resting on a high shelf. But the first time the orchestra struck up the eleven o’clock number and the audience leapt to their feet, some of us danced in the wings, as moved and surprised and exuberant as the audience and the actors and musicians on stage. Over the next few years, we filled the space with our stories as we merged to tell a single story on stage. The members of the audience would then walk away with a new story of their own.

The silence of the theaters around the world seemed deafening.

I haven’t worked on Broadway for six years, but I hear that the ghost lights remained lit on the empty stages of the empty theaters throughout the pandemic, when Broadway shut its doors. The silence of the theaters around the world seemed deafening. At the time I thought it signaled, in its metaphoric way, the momentary end of collective storytelling. But once again, audience and actors and the people behind the scenes are gathering to witness and create our collective story. What I learned is that story, egoless, invisible, and humble, lives on. We will, eventually, find a way to come back together. Our stories depend on it.

University of Maine Farmington