Remembering Vijay Tendulkar’s Ghashiram Kotwal

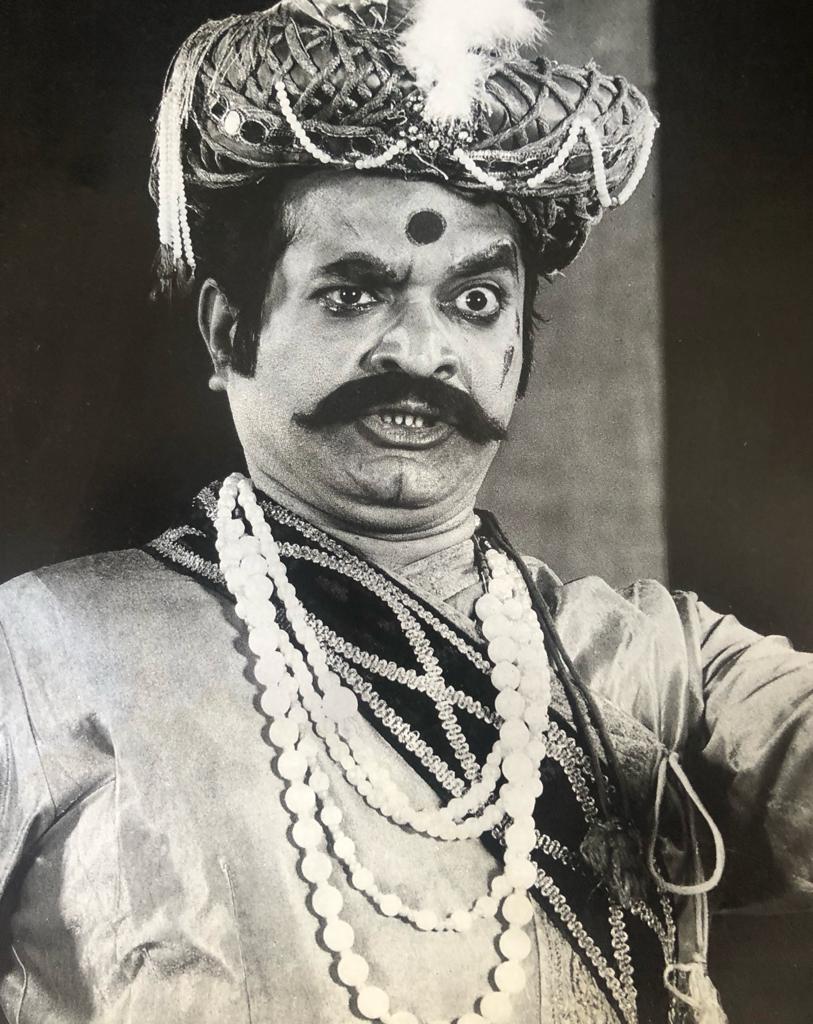

Play Images: Umakant and Shriram Shirodkar

A playwright in Pune, India, considers the contemporary relevance of the fifty-year-old cult play that remains one of the most written about and discussed plays in the history of modern Indian theater.

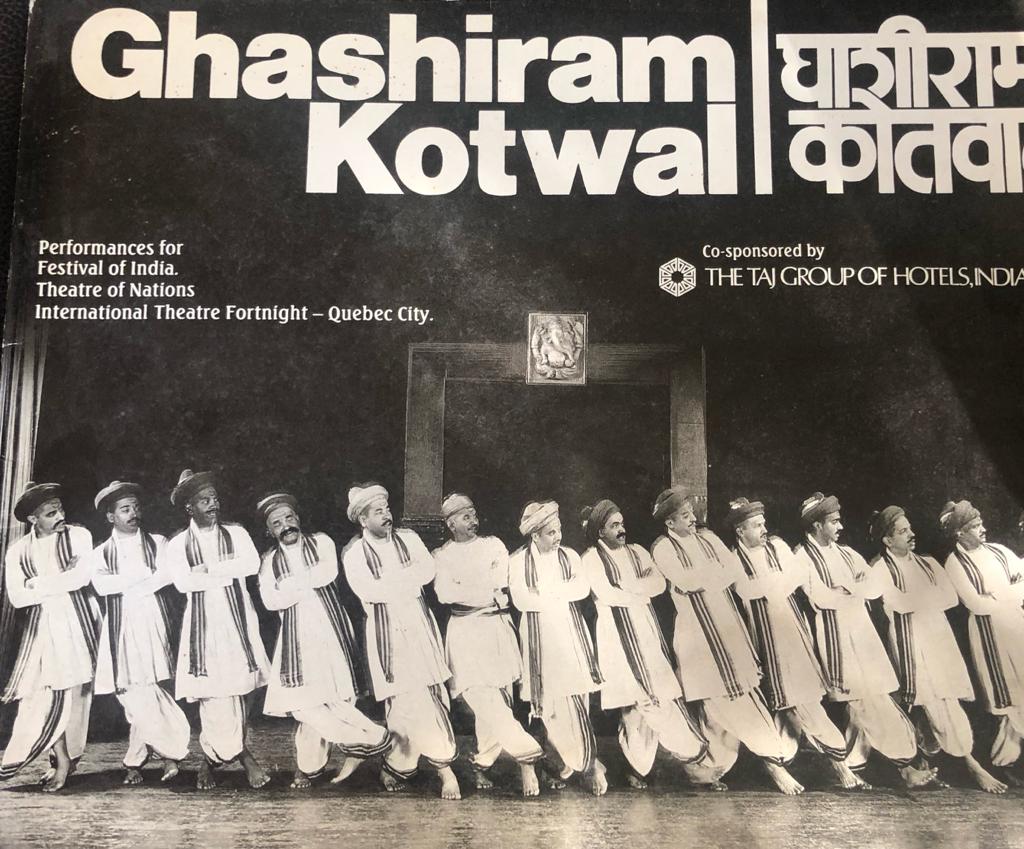

Ghashiram Kotwal (1972), the Marathi play written by one of the finest playwrights of modern times, Vijay Tendulkar (1928–2008), has been around for fifty years now as an inspiration. It was first performed by the Progressive Dramatic Association (PDA) in 1972, and then by Theatre Academy, an ensemble of Marathi performers with a track record of critically acclaimed plays. The play had an electrifying presence on the stage as it toured the world before it was pulled out in the late 1990s. It would be difficult to find a theater enthusiast who has never heard of the cult play, which remains one of the most written about and discussed plays in the history of modern Indian theater. Every time I read the Marathi text of Ghashiram Kotwal, as well as its English translation by Eleanor Zelliot and Jayant Karve, I find it visceral and scathing. As a writer, I am amused and inspired by its simplicity, structural sense, range, and elegance.

As a writer, I am amused and inspired by its simplicity, structural sense, range, and elegance.

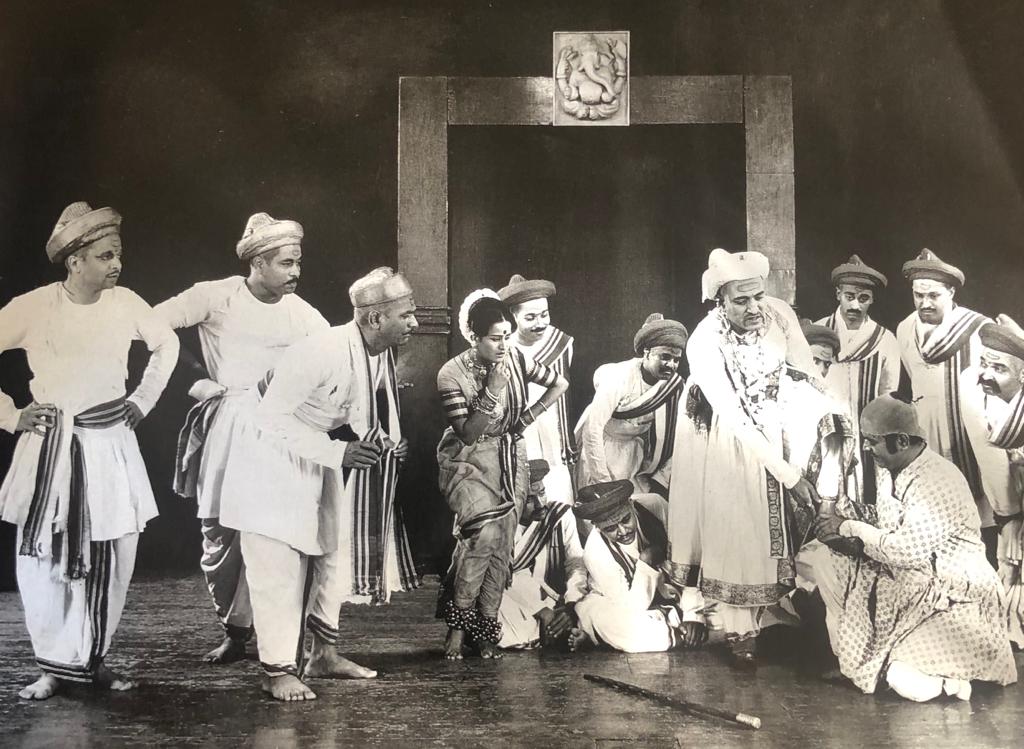

Set during the late eighteenth-century Peshwa history of Baji Rao II and his chancellor, Nana Phadnavis, Ghashiram Kotwal is an intricate design of dance and music, of words and movements. A minor figure from history, Ghashiram Savaldas was an outsider to Pune, a city located in the Indian state of Maharashtra, known for being a stronghold of the Peshwa empire. Salvadas, who came to Pune to make his fortune, is a central character of the play.

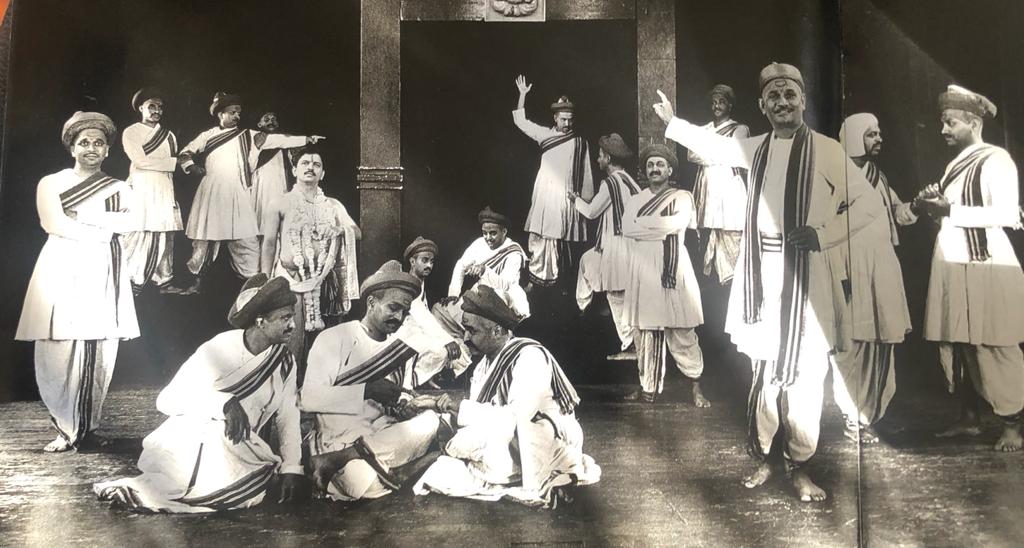

The first act is about the emergence of a falsely accused ordinary Ghashiram Savaldas as Ghashiram Kotwal, a police chief of Pune. The second act is about merciless Ghashiram’s vengeful act, his end, and the decline of his power. However, the play is not a mere recounting of the story of Ghashiram, Nana, and their surroundings; it is a dramatic reflection on the power and violence in the mind and actions of individuals and society at large. Tendulkar makes clear that Ghashiram Kotwal is not, as Samik Bandyopadhyay quotes Tendulkar in his “Note on Ghashiram Kotwal,” “a historical play. It is a story, in prose, verse, music and dance set in a historical era. . . . I have no intention of commentary on the morals, or lack of them, of the Peshwa, Nana Phadnavis, or Ghashiram. The moral of the story . . . if there is any, may be looked for elsewhere.”[i]

Ghashiram Kotwal began its celebrated and controversial run at a theater in Pune, Bharat Natya Mandir, on December 16, 1972—the twenty-fifth year of India’s independence and the twelfth year of Maharashtra’s statehood. While the original production of the play is no longer staged in theaters, the play lives on through the stories that surround it. One such story centers on the controversy of the play attaining second position at the state-level competition, an influential event in the proliferation of modern dramatic activities in Maharashtra. Controversies surrounding the play only intensified in later years, as Ghashiram Kotwal was accused of hurting the sentiments of the Brahmans living in Pune.

The first performance of the play was directed by Jabbar Patel; Ramesh Tilekar played the role of Ghashiram Kotwal, Shriram Ranade performed the narrator, Mohan Agashe played Nana Phadnavis, while Brahmans on the stage were dynamic actors of the Theatre Academy. In later years, the members of the ensemble went on to pursue remarkable careers in their respective fields in theater, music, and cinema. Soon the PDA pulled the production of Ghashiram Kotwal out of theaters, because they were concerned about the play having an inaccurate representation of Nana Phadnavis, and how this might hurt the sentiments of certain members in society. But the young brigade of the playing cast didn’t budge. Breaking away from the PDA, they formed Theatre Academy, rehearsed the play again, and reopened it.

The Pune-based Theatre Academy not only continued to tour with Ghashiram Kotwal in India and abroad, but they also performed several brilliant productions such as Satish Alekar’s Begum Barve and Mahanirvan, among others. Importantly, Theatre Academy didn’t limit their work to only producing and traveling with the plays. They also developed well-programmed activities to support a network of theater practitioners and groups, invited several performances and artists in different languages from across India to small towns and cities in Maharashtra, and introduced a newer generation of playwrights and directors through the various collaborations, workshops, and schemes.

Depicting power relations of different kinds, Ghashiram Kotwal stunned society for its investigative approach in looking at human relationships within broader historical, political, and social contexts. Layering history, performative traditions, and politics, the play became a work of art putting together context and content in a synchronized manner. The well-knit play based on the regressive individual and society shows how the powerful and the powerless negotiate as a means to an end. It’s about how the weak, when drunk with power and given authority, end up exploiting the weaker. And about how the powerful hide behind the weak to weaken them further. Thus, the hierarchy between the powerful and the powerless is not a simple one. It is embedded in the power systems and social configurations of class, caste, and gender. In a deeply cynical way, the play mirrored the individuals and the society that caused violence. That’s why it created an outrage among the upper castes and privileged sections in the society.

Interestingly, while depicting the end of the dark, oppressive Ghashiram, Tendulkar was interested in the system that created and helped Ghashirams to grow. This is one of the unusual and contemporary aspects of the play—it doesn’t give any straightforward message. Instead, it engages with the complexities in human society, ambitions of an individual, the arrogance of the establishment, and the violent manipulations of the dominating class and caste. Ghashiram Kotwal is a historical play, but it refrains from glorifying history; it’s a social drama without a moral message.

Ghashiram Kotwal exists at the nexus of theater, politics, and power. The play might seem too entertaining to some, too experimental to others, or far too political to others still. Thoughtfully, Ghashiram Kotwal finds its expression through the traditional performance practices, folk theater, and the experimental theater that strongly emerged in post-independence India. It has a coherent structure, impactful spectacle of scenes, flexible settings, and well-choreographed movements. Its form emerges from the human actions through singing, dancing, breaking into grouping and regrouping, and it uses the device of the sutradhar or the narrator to connect the different episodes in the story. This was unlike other plays written at that time or before.

Ghashiram Kotwal exists at the nexus of theater, politics, and power.

Ghashiram Kotwal marks an evolutionary point in the experimental theater produced by the amateurs—theater-makers with limited or no funding rehearsing and performing after regular daytime work—in Maharashtra in the 1970s. Increasingly since the 1940s, Indian society had started reflecting on the art of theater, theatrical skills, and the position of theater within a community. They discussed different topics such as playwriting, theater training, an actor’s riyaz with the body, movements and discipline, and the director’s engagement in presenting a play. The content of a play, a writer’s craft, the actor’s preparation, and the possibilities of a dramatic presentation were being thought through within the contexts of the long-surviving Indian theatrical traditions and practices of Western theater.

A new breed of artists and a theater-going public had emerged by the time Ghashiram Kotwal came into being. Moreover, Vijay Tendulkar’s loyal readers were somewhat prepared for the stir that it would create, as he had already set the tone with his brilliant plays such as Silence! The Court Is in Session (1967), The Vultures (1970), and Sakharam Binder (1972), among the repertoire of his more than thirty plays, a number of short stories, film scripts, and other genres of fiction and nonfiction. The experimental zeal in Tendulkar’s writing bloomed in the midst of the dynamic regional practices, emerging avenues for theater training with the theater school like the National School of Drama, the new wave cinema and visual arts, and the revolutionary ideas of Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar.

Although in the last fifty years Indian theater has traveled widely, blurring boundaries of amateur, experimental, and professional practices, amateur theater remains at the core of theater in Indian cities and small towns. Why does Ghashiram Kotwal attract us today when not just amateur theater but different practices of theater are losing their sheen and falling prey to changing economies, market systems, and the interests of individuals?

Ironically, we reminisce about Ghashiram Kotwal, a play that was fervent in its questioning of the past. In his reflective essay published in the theater journal Samantar in April 1998, director and actor Atul Pethe writes that Ghashiram Kotwal has become a kavach kundal, a protective gear. Like Pethe suggests, I feel the play has become a kavach kundal to celebrate the spectacle of Ghashiram Kotwal while protecting ourselves from the spirit of inquiry and exploration of new ideas of drama.

The play reminds us to remain open to investigating the past and envisioning a new world within a fearless society.

Is it out of nostalgia that we are celebrating the existence of Ghashiram Kotwal in today’s time? Is it to remind ourselves that the theater of amateurs has moved away from asking uncomfortable questions of society while entertaining the audience, like Ghashiram Kotwal did? Does Ghashiram Kotwal make us worryingly aware of the newly emerging Ghashirams, and the concentration of power in the hands of the state and its increasing censorship in our daily lives? Do we play Nero by recounting the glorious days of Ghashiram Kotwal when society goes up in flames, as freedom of speech and action is being compromised? Ghashiram Kotwal will continue to haunt us if we play it safe by being selective in recalling how it enamored the public. The play reminds us to remain open to investigating the past and envisioning a new world within a fearless society.

Pune, India

[i] Vijay Tendulkar, Collected Plays in Translation (Oxford University Press, 2004), 586.