London, the New Capital of Middle Eastern and North African Arts, Culture, Music, and Literature

London-based writer Malu Halasa canvasses the Middle Eastern and North African culture scene in London, where even in lockdown, there’s still much to experience.

London makes travelers think of high tea and empire. For those of us who live here and have a passion for and write about the Middle East, London has emerged, more than New York or Paris, as a capital of Arab and Iranian culture outside the region.

London has emerged, more than New York or Paris, as a capital of Arab and Iranian culture outside the region.

It was not always like this. In the 1990s, relatively few Middle East–related events took place in London. Yet in the past twenty years that I’ve lived here, London has been transformed.

The change started taking place in the 2000s. In part, political events, 9/11, and, ten years later, the 2011 Arab Spring or Awakening, as well as the wars in between and after 2011, prompted writers, journalists, and activists to forgo the usual conversation about winners and losers of regional conflicts. Instead, we began to look to creative expression from these countries and in the diaspora for a different kind of understanding and engagement.

It was an approach that continued the conversations many of us were having with the people and voices that came onto the streets and in the squares during the Arab Spring. After the revolutions turned into quagmires, Middle Eastern literature, art, and culture developed a momentum of its own, regardless of news cycles. In many ways, lockdown has been an opportunity for what is made or shown in London to reach global audiences, and usually for free.

The Story of Culture in Buildings

Initially, British diplomats who had served in the Arab world founded the Arab British Centre, which operated a rambling five-story mansion in Kensington, West London. Going there was like stepping into a black-and-white John Le Carréfilm. There was a grand if not decrepit reception room, but behind the public face, the mansion was a warren of offices and rooms, filled with political groups and publications. I spent most of my time in the basement. These were the days before the internet, and in the newspaper clippings and magazine storage boxes I first read Israeli articles about my cousin who hijacked a plane in 1972.

Eventually the Arab British Centre moved to a building north of Fleet Street, a stone’s throw from Dr. Johnson’s House. Today the organization’s cultural remit is both pragmatic and hip, from fashion, film, and digital art to courses on Arabic, oud, and Islamic art and architecture.

There’s a lift in the building, but taking the stairs is far more interesting. Artwork covers the walls. Above the Arab British Centre’s library on one floor is Banipal: Magazine of Modern Arab Literature, where Margaret Obank and Samuel Shimon have been publishing Arabic literature in translation since 1998.

On another is Shubbak: Windows on the Arab World Festival, which takes place in venues across London every two years. The festival not only puts on the latest theater, art, live performance, dance music, and film from the Middle East and North Africa for a frantic two-week period, but it develops new work and draws on the London-based community of Arab theater-makers, like the playwrights Hassan Abdulrazzakand the actor/producer Alia Alzougbi.

The festival’s literature component, curated in the past by translator Alice Guthrie, has brought new Middle Eastern writing, from sci-fi to queer fiction, to the British Library, where I appeared in conversation about my debut novel, Mother of All Pigs. Now Shubbak online features open calls for artists, panels on heritage and contemporary art, and tributes to writer and feminist Nawal El Saadawi, who recently passed away.

Pushing Boundaries

For over thirty years, seminal Middle Eastern fiction and nonfiction have been available in London. Saqi Books, which means “water carrier” in Arabic, is a bookstore and publishing house co-founded by Mai Ghoussoub and Andre Gaspard in 1978.

Saqi, ahead of its time, published titles few Arab publishers would touch, such as Mai Ghoussoub and Emma Sinclair Webb’s Imagined Masculinities: Male Identity and Culture in the Middle East (2000), Brian Whitaker’s Unspeakable Love: Gay and Lesbian Life in the Middle East (2006), and Ammar Abdulhamid’s debut novel, Menstruation (2001). Under Lynn Gaspard, the Saqi tradition of pushing boundaries continues, with the recent publication of Selma Dabbagh’s We Wrote in Symbols: Love and Lust by Arab Women Writers and Raphael Cormack’s Midnight in Cairo, about Egypt’s racy and roaring 1920s.

Saqi, ahead of its time, published titles few Arab publishers would touch.

Vital to London’s cultural mix have been the film festivals: Arab British Centre’s Safar Film Festival, the BBC Arabic Film Festival, and the annual London Palestinian Film Festival, held at the Barbican Centre. The news of the first Tunisian film nominated this year for an Oscar—The Man Who Sold His Skin, directed by Kaouther Ben Hania—reveals the forward programming at the French Institute, which has been screening new Tunisian cinema, courtesy of the British Tunisian Society

Also interwoven in the city’s cinematic engagement with the region is a community of feature filmmakers who live in London, like Zeina Durra, who directed Luxor>, and Basil Khalil, whose hilarious short Ave Maria is streaming on Vimeo. There is also a strong community of Arab women documentary makers: with Claire Belhassine and her family memoir about her Tunisian grandfather, Man Behind the Microphone; Yasmin Fedda and her film about Syria’s disappeared, Ayouni (“My Eyes,” in Arabic); and film producer Dana Trometer, known for bringing rare, hard-to-get footage out of the region and onto the evening news. To honor her father, the legendary editorial cartoonist in Lebanon, Trometer, created the Mahmoud Kahil Award, which gives prizes to Middle Eastern cartoonists, graphic novelists, artists, and illustrators and holds events in London and Beirut.

Eccentric Angles of Creativity

At a time when all of London’s venues are dark, some live event promoters are waiting for the lights to come back on. Aser El-Saqqa’s Arts Canteen organizes Arabs Are Not Funny stand-up comedy nights and the annual AWAN (Arab Women Artists Now) festival, where a Saudi spoken-word artist once performed a piece she was unable to do in her own country, and wouldn’t allow the filming of her performance in case it ended up on social media back home.

Online, the London-based concert producers and organizers of alternative and underground Arabic music, MARSM, have become the go-to place online for the newest sounds from Ramallah to Khartoum. Its site features articles, films, mixtapes, podcasts, and playlists, including No. 31, “Songs for Mothers,” posted for Mother’s Day.

Throughout London, galleries large and small fuel a growing fascination with Middle Eastern art. The Mosaic Rooms, an outpost of the A. M. Qattan Foundation in Ramallah, has a gallery and an extensive events program, which features music, literature, film, and sometimes cooking. The P21 Gallery, too, explores Palestine and beyond, from fashion in Gaza to new Syrian painting, and has emerged as a working space for art activism taking place in Britain.

Also part of the glue in London’s ecosystem of organizations, cultural collectives, and festivals is the British Museum, through the work the museum’s Middle East curator, Venetia Porter. In 1989, when Porter first joined the museum, it collected contemporary Middle East and North Africa as part of the ongoing story of “Islamic art.” By pursuing the ethnological at the expense of the aesthetic, the art lost its individuality and cultural specificity.

Since 2006, Porter’s innovative exhibitions unhinged the artists from the mantel of religion, and they have emerged as a contemporary movement in their own right. In May, the collection will be exhibited for the first time in the museum as Reflections: Contemporary Art of the Middle East and North Africa—if Covid rules allow museums to open.

In the run-up to Reflections, the British Museum organized panel discussions. One of them, “Art Has No Country,” presented by Jo Glanville, included two artists from the exhibition, Afsoon and Mahmoud Obaidi, with Almir Koldzic, head of the refugee arts organization Counterpoint Arts. Their discussion opened with the problem of putting art in categories, whether it is “Middle Eastern” or “Islamic.”

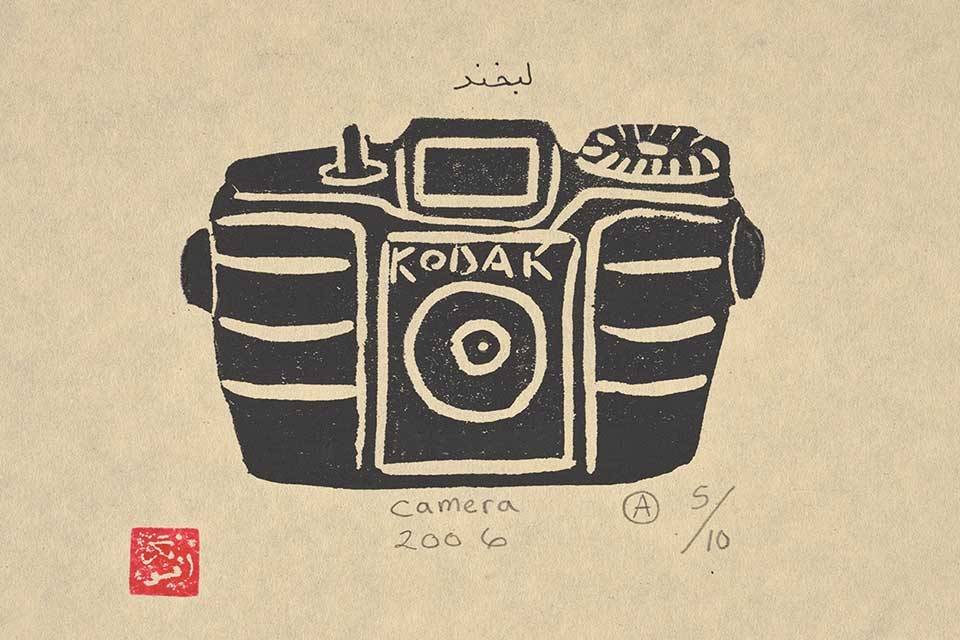

Labels suggests a unity, where there is none, as Glanville points out in the discussion now available on YouTube. The two artists are a case in point. The prints of a camera or a cassette tape by Afsoon, objects pertinent to her memories of growing up in Iran, are very different from handmade books in boxes by Mahmoud Obaidi, which document specific periods in the artist’s peripatetic life once he left Iraq in 1991. For both artists, labels, nationalities, and identities were, at different periods in their life, useful and bothersome.

Almir Koldzic, from Counterpoint Arts, agrees. For him, artists in exile or the diaspora have to find “home” wherever they may be and, unburdened by loss, are free to imagine “eccentric angles of vision.”

Their discussion also spoke to London’s moving feast of Middle Eastern culture. With many eccentric angles on, of, and from the region, horizons broaden.

Politics and Art

Local universities have been generators of research, discussion, and dissemination of the latest work. For regional social and political research and visual criticism, the Middle East Centre at the London School of Economics (LSE) is a vital resource, with its open-to-the-public and online book launches and lectures. Recently, the center’s lively blog page published a research paper on billboards and neoliberal advertising in Palestine. Through visual culture, one encounters different aspects of a place.

However, for those who miss the purely political, the independent foreign affairs think tank Chatham House at the Royal Institute of International Affairs offers webinars.

Contemporary photography is one medium that binds London to Tehran.

It is not only in think tanks that critical thinking on the Middle East takes place. Contemporary photography is one medium that binds London to Tehran. Since 1979, London has provided a much-needed space for Iranian artists. In her large-format, black-and-white photographs, Mitra Tabrizian takes a critical view on the Islamic Republic, in terms of Western involvement and national self-harm. London has also been a second home to the iconic Iranian photographers Kaveh Golestan (1950–2003) and his wife, Hengameh Golestan.

Through the platform Archeology of the Final Decade, the curator Vali Mahlouji has been working with art institutions in London and around the world in “recovering erased histories.” AOTFD “identifies, excavates and re-circulates artists, artworks, and accounts of culture, which have otherwise remained obscure, been subjected to censorship, lost, banned, endangered or deliberately destroyed.” Mahlouji was instrumental in Recreating the Citadel, the first room dedicated to an Iranian artist at Tate Modern, Kaveh Golestan and his portraits of Tehran prostitutes, an exhibition that went last year to the Asia Culture Centre in Gwangju, South Korea. AOTFD also contributed revolution and war photographs by Golestan, and photographs from the Witness ’79 series by Hengameh Golestan, the last day women were unveiled in Iran, to Epic Iran, yet another major exhibition in London waiting to open at Victoria & Albert Museum due to Covid rules.

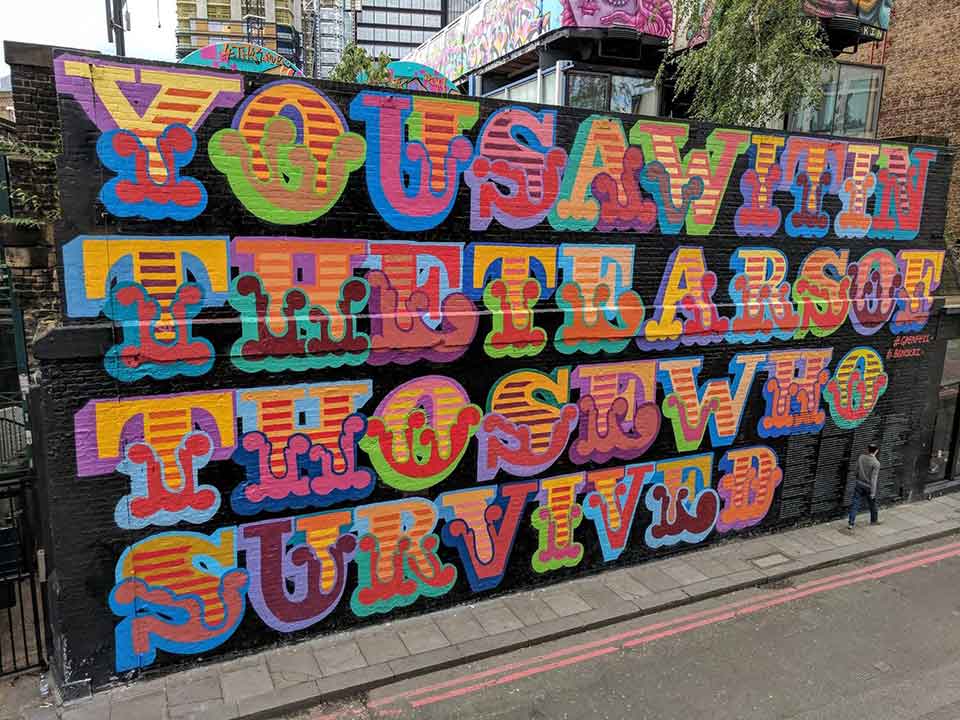

Also based in the city is Maziar Bahari’s IranWire website, which covers politics and trends inside in Iran but with a twist. Alongside hard-hitting reporting and documentary films, the site has always included editorial cartoons and extensively covered the arts. Recently, it made a graphic novel about the first year of the pandemic, The Crash, Covid-19 and Other Iranian Stories, by Mana Neyestani, available as a free download. IranWire also initiates art interventions and campaigns. For Education Is Not a Crime, large-scale murals were painted on buildings in London and cities around the world, to protest the educational restrictions placed on the Baháʼí, a religious minority, in Iran. More recently, IranWire’s #PaintTheChange campaign focuses on British issues.

* * *

Whether you live in or outside of London, the latest Middle Eastern and North African art, sounds, literature, and performance are as close as your computer screen. Before the first lockdown, a year ago, people used to meet for a Turkish coffee or sweet mint tea in Little Arabia along Edgware Road. Although the shisha cafes aren’t open now, it is only a matter of time before they are. Until then, there is much online to watch, listen, and laugh along to.

London