Korean Crime Novels, “The Next Big Thing”?

In his address to the International Association of Crime Writers 2013 meeting in Oxford, Christopher MacLehose commented that publishers like him are always looking for the “next big thing” for mystery readers. The “big thing” at that time was “Scandi noir.” Building on the success of Henning Mankell’s Wallander series and Stieg Larsen’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, a tidal wave of Scandinavian noir had surged into British and American translation, and continues to, as more and more Scandinavian authors reach our bookstores. An author with a Nordic name and a certain style is automatically of interest to publishers of translations. Inevitably, these unpredictable tides rise and fall. The similarities of any form can become too familiar or the quality diminish as more peripheral writers and imitators exploit its popularity. What a society finds compelling may change, and readers weary of authors’ tricks and become restless for something different: “the next big thing.”

At the time of his address, MacLehose believed that the next wave would come from France. Pierre Lemaitre’s shocking thriller Alex had made a big splash, and the French were revitalizing their style of noir through inspiration from Mediterranean writers like Jean-Claude Izzo. Lemaitre’s next translations, Camille and Irène, were also successes; however, despite the long history of innovation and influence in the French crime novel—from Émile Gaboriau to Georges Simenon to Didier Daeninckx—a new wave seems not to have materialized. The Wall Street Journal appears to have been a little more prescient in 2010, predicting Japan as the next “hot spot.” To the stereotypical geographically impaired American, the distinctions between Finns and Norwegians is often obscure, and the differences among Far Eastern cultures are even more vague. Asian crime writers, however, are currently attracting much more attention than they ever have. The Far East just isn’t as far as it used to be. Asian culture and settings have become more than merely colorful clichés among English-language writers familiar with these nations. There are many examples. Chinese American author Lisa See’s Dragon Bones (2003) blends Chinese history into a murder mystery at the Three Gorges Dam. Francie Lin’s The Foreigner (2008), set in Taiwan, won a Best First Novel Edgar. Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son (2012), set in North Korea, won the Pulitzer Prize. Now residing in Oklahoma, immigrant Vu Tran portrayed the experiences of Vietnamese refugees in the form of a highly praised detective novel, Dragonfish (2015). Qiu Xiaolong, born in Shanghai, now lives in St. Louis and is also an Edgar winner. His series of nine Inspector Chen Cao novels since 2000 has sold millions of copies (see WLT, Jan. 2012, 23–27). Each of these writers, and several others, has contributed to making readers more receptive to trying out translated Asian crime writing.

The Far East just isn’t as far as it used to be.

To the surprise of many readers, however, recently much attention has turned toward the inventive range of authors from South Korea, and several translations in particular have gathered much literary recognition. The Vegetarian, by Han Kang, and its translator Deborah Smith, won the Man Booker International Prize for 2016 (see WLT, May 2016, 62–67). A short novel that has the surreal quality, it seems to me, of many works by Japanese author Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, it turns the simple act of a woman’s choosing vegetarianism into a destructive challenge to her husband and traditional family. Japanese fiction is popular and influential in South Korea. Publishers enthusiastically seek the translation rights to crime authors such as Keigo Higashino and Kotaro Isaka. Japan, long a major player in crime fiction, probably had a significant role in drawing English readers’ attention to other Asian authors in the last two decades with novels like those of Natsuo Kirino and Tetsuya Honda.

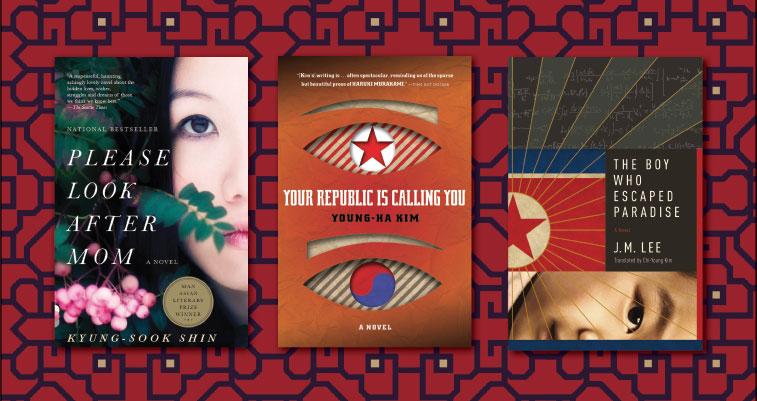

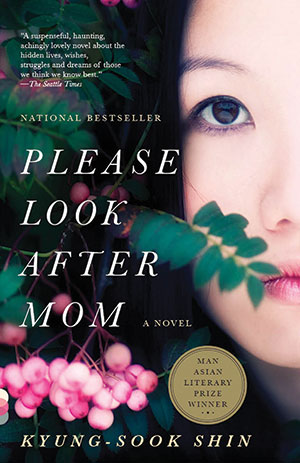

Please Look After Mom, by Kyung-Sook Shin, was another novel that helped Korean writers break through the language barrier. It won the 2011 Man Asian Literary Prize (along with translator Chi-Young Kim) after selling over a million copies in Korea in less than a year and many more in translation after Oprah Winfrey blessed it. Minutely examining the relationship of a mother to her children and husband, it also confronts the duty of obligation to family, to the point that it was compared to Stella Dallas and Mildred Pierce, as being weepy and overly melodramatic. “Kimchee-scented Kleenex fiction,” Maureen Corrigan said notoriously on NPR, causing an uproar. However, Shin’s novel became a best-seller despite unusual stylistic tricks that are not usually a part of best-sellerdom, like telling the story in multiple points of view and using mostly second-person narration.

Also known for his inventive use of style is Kim Young-ha, the author of I Have the Right to Destroy Myself, which introduced him to a global audience in French translation in 1996. It is the story of a love triangle involving two brothers but exposes a perverse obsession with suicide and hidden desires. Kim began writing after serving in the military for two years as an assistant detective and is highly prolific. He has over two dozen novels currently being translated despite his being under fifty years of age. In 2004 Kim swept the three most important Korean literary awards and established a reputation as the most talented young Korean author. He often incorporates crime-writing elements, and the word “noir” frequently pops up in commentaries about his work. Your Republic Is Calling You (translated in 2006), for example, sets the stage for a spy thriller and takes place in a twenty-four-hour period. Yet, like all the best spy fiction, it raises much larger questions. A deep-cover North Korean agent has lived in the south for half of his life, having last heard from his superiors more than a decade ago. He is leading a normal life—he has married and has a daughter—but he receives a mysterious unexpected email leading him to orders from his handlers to return to Pyongyang. He has no idea why. He cannot even be certain that the message is genuine. Could it be a trap? It could simply be the end of his mission, whatever it was, or it could be that he has been judged unfit and will return to his execution.

More conventional Korean crime writers are also getting translated. J. M. (Jung-myung) Lee is an exceptional one of these. He has sold millions of copies in Korea and been adapted for television. He has earned growing enthusiasm in translation since the appearance of The Investigation, translated by Chi-Young Kim and chosen a 2015 “top pick in mystery” by Vanity Fair. The impact of World War II still resonates powerfully in Korean society, where, for example, the issue of “comfort women” is still controversial. There was virtually no interruption between the Japanese colonial period, struggles for independence, World War II, and the partition of the peninsula, which all must seem like a multigenerational nightmare. The Investigation centers on a main character who serves the Japanese empire as a prison guard during the war. When one of the other guards (nicknamed “The Butcher”) is murdered, Watanabe Yuichi is assigned to investigate and finds a poem in the victim’s pocket. The Butcher, it turns out, had a literary penchant and had become a friend of prisoner and poet Yun Dong-ju, a character based on a real Korean poet. This allows Lee, to greater or lesser effect depending on your taste, to weave in Yun Dong-ju’s poems and introduce English readers to his writing while the mystery is being solved.

More conventional Korean crime writers are also getting translated. J. M. (Jung-myung) Lee is an exceptional one of these. He has sold millions of copies in Korea and been adapted for television. He has earned growing enthusiasm in translation since the appearance of The Investigation, translated by Chi-Young Kim and chosen a 2015 “top pick in mystery” by Vanity Fair. The impact of World War II still resonates powerfully in Korean society, where, for example, the issue of “comfort women” is still controversial. There was virtually no interruption between the Japanese colonial period, struggles for independence, World War II, and the partition of the peninsula, which all must seem like a multigenerational nightmare. The Investigation centers on a main character who serves the Japanese empire as a prison guard during the war. When one of the other guards (nicknamed “The Butcher”) is murdered, Watanabe Yuichi is assigned to investigate and finds a poem in the victim’s pocket. The Butcher, it turns out, had a literary penchant and had become a friend of prisoner and poet Yun Dong-ju, a character based on a real Korean poet. This allows Lee, to greater or lesser effect depending on your taste, to weave in Yun Dong-ju’s poems and introduce English readers to his writing while the mystery is being solved.

Lee’s latest publication in the US is The Boy Who Escaped Paradise (2016), also translated by Chi-Young Kim. Ahn Gil-mo, an autistic math genius, is connected to a murder in New York City and, because he escaped from a labor camp in North Korea, is investigated by a CIA agent who tries to grasp his unusual thought processes. Through a week of questioning and a series of mathematical puzzles, Gil-mo reveals a number of crimes he was involved in during his long journey from imprisonment in Korea, through China and Mexico, and into New York. In many ways Gil-mo, with his unusual ways of seeing reality, becomes a Prince Myshkin kind of idiot, revealing the world for what it really is, if we only had the simpleness to see it.

Perhaps the “next big thing” is not an issue of nationality but rather being open to allowing authors to blend and merge their own unique qualities and cultural assets into the variegated flow of world culture.

Another “Korean” crime novel earning much attention on its publication in 2003 was The Interpreter, a first novel by Suki Kim, and I mention it for a particular reason. The story of a courtroom interpreter in New York City who seeks to solve the mystery of her parents’ murder five years before, Suzy Park’s search in the shadows of the community’s underground culture becomes an odyssey of the self, another examination of the Korean themes of familial duty and identity. Why I single it out, however, is because it occurs in the context of immigration. The main character is torn between cultures. Like the author, she was born in Korea but raised in the United States.

Kim has written for the New York Times, Harper’s, and other periodicals. Her first book, Without You, There Is No Us, was nonfiction, based on her experiences undercover teaching English to the children of North Korea’s ruling class. Should we consider her a Korean author or an American author or some sort of chimera? Does it matter? Perhaps the “next big thing” is not an issue of nationality but rather being open to allowing authors to blend and merge their own unique qualities and cultural assets into the variegated flow of world culture. Isn’t this what has been happening in crime writing? American noir becomes a different shade of noir in Scandinavia and then returns through France and Britain and Japan to change the color of American noir. The inventiveness and styles of the Korean crime fiction coming to us seem to offer a whole new palette.

Palymra, Virginia