Two Poems

Letter to Baghdad

Even if my father never speaks a word of it, I will know

he brought a candle, a cough, and the occupied side of his heart.

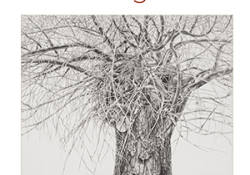

I will know the trees held him, that they rose above rooflines,

and where they met, he climbed and saw roads paved only with praises.

The sun he carried across oceans turned copper at his window.

I saw it too, on the gray edge of my childhood,

and I was marked when each day awoke. He devoured the silence,

the parts that could not be cured, and when he was hungry for it,

I swallowed the silence, his self-portrait of confession.

When I found an old shawl and silver teapot in the oven,

and he pretended he didn’t know what they meant,

I remembered bitter lemons had moistened his mouth.

What he inhaled from his copious memory

left his tongue empty then full, and somehow I know

his tongue will always be brushed with the leaving.

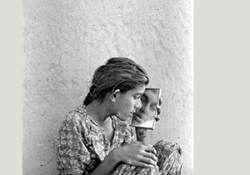

One day we were talking about beginnings, and I had begun.

I wasn’t at the center anymore, and we kept letting in a little air,

and he showed me a word for the boy he once was

and he showed me this Arabic word and in this way I knew

this was the most authentic mourning I would ever see.

And I saw it and he said it again,

and we were covered with it. Entirely covered. This was his home, he said,

as he gave me the address, the place

where the first time and the spurned and the color

and the milkmaid stood in the alley. And even though he didn’t tell me

about yesterday and the day and the day and I never saw

any other way to tell it I never saw

heaven or the land that was black, one day I knew enough

to take the word from him and drink my fill

of everything every little thing every steeped thing

and there were many trees and not enough cold and we sat

by the river that curves in every direction and our hearts

lifted up to the birds.

Why Dad Doesn’t Pay Attention to Iraq Anymore

You can all stop asking about the Abu Ghraib torture

and how he felt when the pictures were published

of men in long hoods. He was traveling

the white rim of traffic from New York

to the city of brotherly love,

stopping for donuts (cream-filled).

When Hussein’s statue fell, he was up in his condo,

organizing pencils, most with erasers.

His radio tuned to Beethoven’s Sixth

or some college football. Collateral damage,

snipers, missiles, vessels, and hostile

attention: he’s not watching.

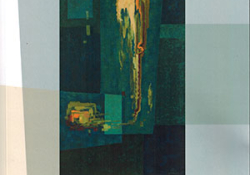

His black shadows are inverted.

His horizon’s a gold minaret. The zip and clatter

of dust. A river branched under

a bridge, then cut from the muscle of land.

He sees the circumference of dates.

Unsaid words pile in dunes.

All he wanted was some portion of yes

and stay, those phrases no one could pack.

The tick talks backward. His single truth

was to stop reading; letters became drifts.

In terrible gutters and columns of newsprint,

the longest griefs are those we never look at.

Anyway, even in war stories, everyone dies in the end.

Editorial note: For more, read Camp's recent blog post ”Surrendering to the Unsaid” where she expounds upon her experience of researching and collecting memories from her father for this collection of poetry.