The Prisoners of the Past

As this story about changing laws and changing times in South Africa reveals, repealing the letter of a law will not necessarily kill its insidious spirit.

Vuyo, the book (which is entitled The Visitor), felt very lonely, cold, and claustrophobic. It was difficult to breathe. This was not Robben Island, but for him it might as well be. The book was in a black plastic packet in a box inside an icy steel cupboard. He had been incarcerated in a basement since 2007. Since then, he had not been touched, held, or opened by anybody but his captor—and then only infrequently. How Vuyo the book missed the library from which he had been kidnapped! It had been such a long time. It was horrible: not to be read, not to be discussed, to be ignored after all the effort that had gone into his creation. It was thoroughly evil, but he was helpless. He was at the mercy of beings who were afraid of what was on his pages. And so they had ensured that he was kept hidden away, incarcerated, away from public view as if he was dangerous.

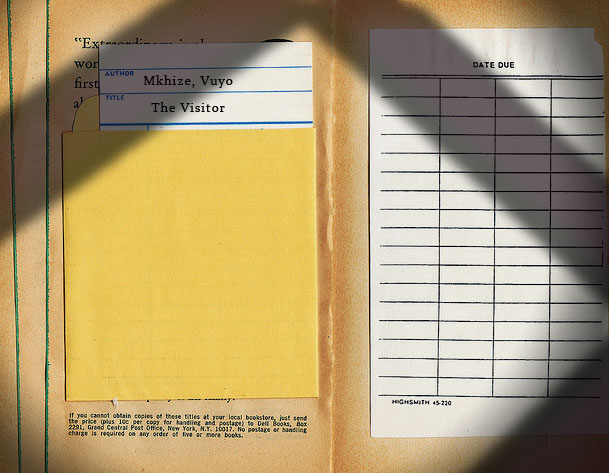

“Good day. I am looking for this book by Vuyo Mkhize. It’s called The Visitor.”

Meritin looked up from the library counter to see a cheerful-looking young black man standing in front of her. He was skinny and so black he looked as if he had been dipped in coal tar.

It was a bright Saturday morning, and the Tegwhite library was buzzing. There were children all over the place, and they would not keep quiet. Meritin noted that, as usual, there were more black people around than white. The overcrowding that had happened after the opening of the libraries to all races had not been expected. Mandela’s release had caused so many changes. This had been a quiet, law-abiding, white neighborhood, but after the laws had been changed, Tegwhite had been flooded by the blacks, who began settling in what was once a pristine suburb.

The middle-aged librarian nodded and called up the book on the computer. “There’s one book in stock; it has not been borrowed,” she confirmed. They walked together to the South African fiction section.

They looked among the books, but The Visitor wasn’t there. No longer cheerful, the black man looked perturbed.

“I tried at the main library as well, but their two copies have been stolen,” he informed Meritin. “The security can’t be too good?”

“Well, there are many ways to skin a cat,” replied Meritin, her face wreathed in a wry smile.

“You think that . . . ?”

Meritin said, in a tone that the man knew so well, “We’ll see what we can do.”

The South African left, his shoulders in a slouch.

***

Khanyile, the book, felt the desolation descend upon her as it usually did every Saturday at about one p.m. when the library closed for the weekend. The steel shutters slammed shut on the library, and the air began to grow heavy and oppressive. Most Tegwhite libraries closed by five p.m. on weekdays and by one p.m. on Saturdays. The Tegwhite libraries did not open at all on Sundays. That law had not changed since Apartheid times.

Khanyile had not been borrowed ever since she had been reclassified and moved to the Poetry and Plays section. Meritin had told a junior librarian, “That Khanyile book is pure theatre. It has so much dialogue. No, it must be reclassified and moved to the Plays and Poetry section.”

Khanyile thought this was a ploy to stop people from reading her. Hardly anyone read plays. Poor Khanyile. The book felt so lonely. It was as if Apartheid had never ended. During Apartheid, authors like Winnie Mandela and Fatima Meer had had their books banned by the government. This reclassification was a new, technically lawful way to prevent readers from reading South African books.

It had been a miracle that she had been published at all. Her author, Jabu, had hawked the manuscript from publisher to publisher over many years, but none would publish her. She was, after all, a novel about the past. Most of the publishers’ readers who decided whether books would be published were people from a completely different social and racial milieu. Khanyile, when she was still a manuscript, had watched the brows of these people furrow as they tried to comprehend scenarios and experiences on her pages that were completely alien to them. More than that, the book included tales about South Africa’s present and past racist turmoil. That really seemed to upset the publishers’ readers.

Jabu had finally found a nonracist editor and published Khanyile at his own cost, borrowing the money to do so by taking a second bond on his home. His family and friends had worked hard to make sure that Khanyile was as flawless as possible. Shibambu, the graphic artist, had designed the beautiful cover. They ensured that the layout was properly done and that the spine of the book had both the name of the book and the name of the author.

However, getting the book into the libraries was yet another big battle for the author. Jo Bann, the chief book buyer for Tegwhite libraries, still observed the previous policies, and she ensured that her libraries were similar to Anglo-American libraries with just a small subsection for South African books.

Jo Bann had made it very clear at a book launch: people want happy, humorous tales, not sad stories about the past. She added, “Even black children don’t want to read about the past. Nostalgia does not sell. Our great author, R. Malace, stated specifically that in his competition he wanted only stories about the present and the future. South Africa needs to move forward. The past can only hold our country back. We must not live in the past.”

Some people in the audience looked perturbed.

Jabu spoke up: “If Jews can write about the Holocaust, why are we being discouraged from writing about what happened to us? After all, Apartheid is supposed to be over. Our books cannot be banned anymore.”

“Well, you can write your books, but we don’t have to publish them, and we don’t have to read them,” said Susan, a publisher who had recently published a best-selling book about cats.

Her outburst reminded Jabu that the the Susans of the world still controlled what people read.

Sad as Khanyile was, she really felt for her dear friend Vuyo. While Khanyile still occasionally experienced the thrill of being touched and even caressed by people interested in what was on her pages, Vuyo was as isolated as Nelson Mandela had been.

How Khanyile missed Vuyo! He was such a fun book. He was full of fascinating stories about all kinds of things—from tales about germs that attacked a doctor who had tried to eradicate their illegal rubbish dump to a story about how, during Apartheid, a poor nonwhite community had donated the land for a primary school and built it. There was even a story about how South African medical students had banded together to stop the Apartheid government from banning black medical students from their Natal University Medical faculty in Durban.

Khanyile’s creator had written about how, many decades ago, laws had been promulgated that libraries should never be open on Sundays, as this was considered to be un-Christian. “This was family time,” supporters argued. “In any case, most librarians are women, and women should be at home when the family is there,” pronounced a lawyer, Mr. Hiter, to the awed librarians assembled before him. The attorney was head of libraries in the national government. In 1965 he made a special trip to Tegwhite because some of the soft-bellied liberals had asked for the libraries to be open when “working people are not working.” They were worried that many people were not reading and that the republic’s educational standards were dropping. The lawyer, however, quickly realized there were only a few troublemakers who wanted to open the libraries on weekends. That the values of the voters were being maintained was proven to his satisfaction by a large sign on the door of the main Tegwhite library: “Europeans Only. No Dogs Allowed.”

The provincial head of libraries in Natal, Richard Tomkis, had stood up at this conference and stated, “Fellow librarians, we do not open libraries on Sundays just as we do not sell liquor and open cinemas on that sacred day; I am sure we all agree that it would be absolutely un-Christian to do so. Please remember, most people who read books are women. They can always get books for those husbands who feel the need to read. Otherwise, people can always go into the library on a Saturday morning.”

Most of the people at the conference nodded their heads at this excellent clip of sagacity.

Hiter added, “There are no libraries in most black townships. And those that have libraries must not be open after hours—that will only encourage the nonwhites to meet and plan all kinds of devilish schemes like getting Mandela released and so on. You know how these Communists are constantly trying to undermine the Christian state.”

Heads kept nodding in agreement.

“We must keep the libraries safe for democracy. Encouraging nonwhites to read can only undermine that.”

Hiter had a few good friends in the secret police. These law men had been busy setting up shebeens (taverns) in the nonwhite areas—places where liquor, addictive drugs, and women infested with venereal diseases were readily available. The shebeens were doing a roaring trade, especially when libraries were closed, and Hiter had recently received a nice “contribution” in cash for his part in making the shebeens just about the only places where nonwhites could go when they had free time in the segregated townships.

***

Meritin looked up on another Saturday morning, and there he was again: the lanky, ebony man who had asked for the Vuyo book. He was smiling at her. “Hello. I have come to meet the principal librarian, Mrs. Becarie.”

“She’s busy . . .”

“I phoned her and she’s expecting me.”

A cheerful voice entered their conversation. “Ah, there you are, Mr Vuyo Mkhize! It’s so good of you to come. It’s always an honour and a pleasure to meet one of our local authors.” Mrs. Becarie walked over from her office and shook hands with the tall man. She had a one-way glass panel on a wall of her office that enabled her to see what was happening at the reception desk.

Meritin thought that he looked very young to be an author, of all things. Her heart went cold. She had never suspected that she had been speaking to the author of the award-winning book The Visitor. He did not look quite like his photograph on the back cover. And how infuriating: The blacks were even writing books these days! When she was a child, many blacks could not even read. Back then she had never dreamed that the blacks would be allowed to vote and take over the country.

Neeta Becarie shook hands with Vuyo and welcomed him into her well-furnished office.

“Thanks for stopping by; I know how busy you must be between your career, your family, and your writing . . .”

They sat down opposite each other at Neeta’s table.

“Yes, life is interesting.” Vuyo smiled his winning smile again.

“I read your book, Vuyo. It’s an excellent read, but I can understand why some who prefer the old days might not exactly like it.”

“That’s a huge compliment, Mrs. Becarie. Thank you.”

“Call me Neeta. I checked about your book, Vuyo. It’s amazing. It’s never been borrowed since we did the book audit in 2007. We did another audit this year and, amazingly, it was in the library. But now, it is again not here.”

Vuyo looked angry. “Really? It looks like the days of banning our books have not ended! Do you think a librarian has taken the book, and in that way stopped the public from borrowing the book?

“It’s sad if a librarian did do that.”

“But I am confused. Why do this? Why not just steal the book? That happened at the central library.”

“I raved about your book even before it got to our library. I think whoever took the book knew that if they stole it, I would ensure that it would be replaced.”

Vuyo nodded. “Thank you.”

“I’ve put the word out that we need the book. It’s almost school holidays. I want to host our local authors. And we want to invite you to meet your readers and potential readers. How does a Saturday morning suit you?”

“I’ll have to make the time.”

“Good.”

“But how can you host me if you do not have copies of the book?”

“I’ll put an order in for two more books with Jo Bann; she’s in charge of book buying.”

“She’s still in charge? But she was in charge during Apartheid.”

Neeta nodded.

***

A few weeks later, Neeta phoned Vuyo to tell him that his book had made a mysterious reappearance at the Tegwhite north library. They arranged a date for him to meet readers at the library.

Vuyo told his friend, Jabu, about what had happened and he, too, came to the library to look for his book, Khanyile. Jabu chatted with Neeta about Khanyile’s classification, and Khanyile was reclassified and reunited with Vuyo. There was much jubilation among the books at the library.

Vuyo, the author, wrote to the newspapers about the need for libraries to be open when working people were not working. Students needed a quiet place to study. Many people’s homes were tiny, and they needed a place where they could study and simply relax, read the newspaper, and get away from the stresses of the world.

Vuyo was fortunate. He met Mr. Redd, the new chief librarian for their district. Mr. Redd had experienced the Apartheid way of life. He empathised when Vuyo explained the situation to him. Mr. Redd initiated a process to change the municipal laws and free the books. Patrons were asked to fill out forms indicating when they needed the libraries to be open.

But many people were upset by this attempt to change what had been the law for many decades, and there was a great deal of resistance to the proposed changes. Rampant criminal activity meant that libraries could be targeted if they were open at night and on Sundays.

***

Meritin sat back in her lounge and gazed at her award from the Centre to Promote Civilization. The fight would continue.

Durban, South Africa

The Author's Inspiration

Three laws inspired this story:

1. The Separate Amenities Act: Under this Apartheid law, all public facilities, from parks to benches to beaches, to public transport, to restaurants, hospitals, hotels, schools, universities, and libraries, were segregated.

2. Group Areas Act: This Apartheid law forced communities to live in separate areas.

3. Sunday Observance Law: This law forbade cinemas, shopping malls, liquor outlets, and libraries to open on Sundays.

Some of these laws fell away even before Mandela was released from prison, but they still have a place in the hearts of those who believed in them. Many still hanker after the “relaxed colonial days.” Those who are now freer resent intensely the laws of the past, now rescinded, which still operate in the minds of those who benefited from Apartheid. Sadly, many of our libraries still close by five p.m. on weekdays and after one p.m. on Saturdays, remaining closed on Sundays. The events described in the story actually happened to my book of short stories—one bookstore classified it under poetry and plays rather than prose, and the book implausibly disappeared and reappeared in a Durban library.

- Deena Padayachee