Playing the Classical Chinese Literati Tradition

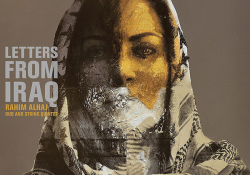

I have great respect for all musical traditions and have enjoyed collaborating in past decades with great musicians from different cultural backgrounds, including African, Arab, Indian, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Western. It was indeed mind-broadening and exciting because such collaboration often involves improvisation.

While music in this context is often about expressing mood and feeling, it is fascinating to experience how musicians from different traditions, who play different instruments, come together thematically. It is inspiring and even profoundly creative, particularly when organizers provide sufficient time for musicians to rehearse before concerts. This is especially true when musicians meet with an open heart, wanting to learn from each other and not simply be satisfied with things just sounding “okay.”

In the contemporary context, it is also a great joy to perform with individual musicians, string quartets, or orchestras where the pieces are mostly composed. Here the challenge, however, is more for the composers than for the performers. It is very demanding for a composer to create a piece for a traditional instrument like the pipa (a four-stringed Chinese lute) that fully explores the typical features of the instrument to such an extent that it would not sound equally satisfying if played on some other instrument, such as the guitar or banjo. This requires the composer to become familiar with the instrument, not just the sound and scales. Amazingly, there are still a number of excellent pieces available by various composers.

For my solo concerts, I play mostly traditional Chinese music from the classical literati tradition, which can be considered as “traditional classical music” in contrast to folk traditions or the entertainment music industry. Traditional classical music refers to art music or “sophisticated” music composed by scholars and literati in China’s historical past. This type of music often has thematic, poetic, or philosophical associations and is intimately linked to poetry. As poetry, it sets out to express human feelings, soothe suffering, purify the mind, or bring spiritual elevation. This type of music was noncommercial, typically played solo on private occasions for oneself for the purpose of meditation or self-cultivation, or for Zhi Yin—literarily translated as “know music,” which has become a synonym for intimate friends and music lovers, on instruments such as the qin (commonly known as guqin), a seven-string zither with over three thousand years of well-documented history, or the pipa, a lute with over two thousand years of history. The music is supposed to be played in a meditative state, and the feeling and energy are present and should remain fresh even when repeating the “same old pieces.”

The challenge here is the current tendency of constantly looking for “new,” underscoring that only the “original and new” music has artistic value, a viewpoint that probably came from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries regarding the artistic value for arts (in particular paintings). While there is nothing wrong with creating new—and indeed, today’s good creation will be tomorrow’s tradition—it is misleading to use this to judge music-making, particularly for music that came from oral traditions. Even for the same piece, if played from a “true self” in the state of meditation, every performance is “original and new,” not to mention the different environments and audiences. In a real sense, one cannot separate music from musician. When the musician dies, his or her music no longer exists. Recording is not the real thing. That is repeating, not music-making, which is very different from painting.