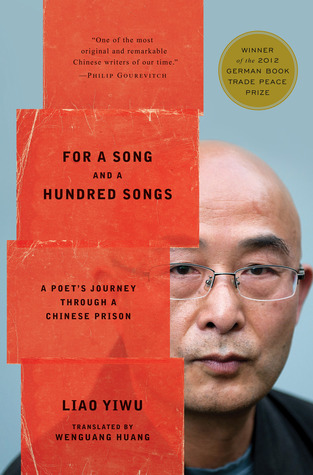

Editor’s Pick: For a Song and a Hundred Songs by Liao Yiwu

For a Song and a Hundred Songs

For a Song and a Hundred Songs

Liao Yiwu

New Harvest, 2013

Though Liao Yiwu is yet another name in a long line of censored Chinese literary and artistic critics like Liu Xiaobo, Ai Weiwei, and Hu Jia, Liao’s personal memoir reaches beyond his own story to capture a small sense of the collective suffering of thousands of prisoners during China’s rise to global power in the early 1990s. Arrested for his criticism of the Chinese government through his poetry and a film screenplay called Requiem, Liao is sentenced to four years inside the Chinese prison system: three months awaiting investigation, two and a half years awaiting trial, and another year and a half serving out his sentence. This book is his first successful attempt (after previous manuscripts were twice seized by the Chinese government) to put on paper his recollections of this turbulent time in China’s recent history (see WLT, Nov. 2009, 62).

Liao’s descriptions of his time within all three institutions are often hard to swallow. Between the violent episodes of various initiation rituals and the general corruption of and abuse by the prison guards, his depictions of life during incarceration are often bleak and convey more than an acute sense of hopelessness. But something in the way that Liao chooses his words—which must also be attributed to his excellent translator, Wenguang Huang—also shows us that there is more than meets the eye within the walls of a prison.

While Liao calls this book a prison memoir, it is not solely about his time in prison. Because of the high turnaround rate within the Chinese prison system in the early 1990s, Liao meets, befriends, or makes enemies of hundreds of fellow prisoners incarcerated for crimes ranging from counterrevolution to murder. And slowly, over the course of the chapters, we come to know these people through Liao’s poetic descriptions of their day-to-day lives.

A single sentence in the book's preface, describing the scrutiny and censorship Russian Nobel Prize–winner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn faced while writing The Gulag Archipelago, gives us the true explanation for the inclusion of these descriptions: “The only way to preserve his writings was to get them published.” It can be difficult to remember or to recognize the fates of ordinary people within China’s prisons when so much is reported about the incarceration of the country’s literary elite. But through the publication of this memoir, Liao has not only preserved his story of abuse and injustice—he has preserved the stories of all the men incarcerated alongside him.

The book comes full circle in the epilogue, where, after his release from prison and while he is rewriting his memoir, one of Liao’s acquaintances from the No. 3 prison tells him, “I hope your book can serve as a testimony to an important part of Chinese history.” Liao’s book beautifully fulfills this ex-prisoner’s hopes, serving as a reminder of the spirit and tenacity of human voices not just wanting or needing, but deserving to be heard.

Kaitlin Hawkins

Social Media Editor