Disrupting the Odalisque: An exchange between Emily Johnson & Lalla A. Essaydi

Emily Johnson, Associate Professor of Russian in the University of Oklahoma’s Department of Modern Languages, Literatures & Linguistics, is a longtime contributing editor to World Literature Today. After seeing Essaydi’s photo-essay “Disrupting the Odalisque” in the March 2013 issue of WLT, Professor Johnson sent us the following questions, to which Ms. Essaydi thoughtfully replied.

Emily Johnson

I loved the special issue on photography. Lalla A. Essaydi’s beautiful photographs did, however, leave me with several questions. What exactly is written on the women’s bodies, their clothing, and the architectural spaces that surround them? Is the text always the same or are specific passages chosen for particular subjects? The essay by the photographer that accompanied the images did not make this clear. Was that a principled choice? The effect certainly was striking: in the pages of a literary magazine, I found myself confronted by gorgeous images in which words seemed to play a primary role, and yet, cut off from the meaning of the text, I could appreciate the words only as visual elements.

Lalla Essaydi

It is an interesting interpretation of my work and the first time I hear someone saying that they can appreciate my work only at a visual level. What about the engaging gaze, the space, the figures, etc.? When I personally look at a painting, or a photograph in which there is no text, I don’t merely see only decorative elements, I try to read the visual language the same way I apply to reading letters of a book. But I understand for a literary magazine people expect to read the words. A few years ago Harvard University’s Department of Languages & Literature used one of my photographs as the cover to their annual magazine, and they had the same questions.

The text in my artwork is deliberately illegible, invented forms that allude to Kufic calligraphy but yield little direct access to information. Thus, the play between graphic symbolism and literal meaning and the largely European assumptions that the written holds the best access to reality are constantly questioned.

The meaning of the text changes according to each photograph. I usually started with a specific text that I had in mind while preparing for each photograph, but later the written text is a response to my surrounding and to the exchange I have with the women in my photographs.

I go to great lengths to make the text illegible. Even those who can read Arabic can hardly decipher the text since the henna, when it dries, changes shape and part of it flecks off, making the text unreadable. I want the text to become a visual language of its own, appreciated in the same way as the figure. It doesn’t necessarily need to have a meaning. But the whole work is autobiographical—written from a personal perspective, it is the story of the women in the photographs as well as my own written in prose, since poetry and architecture are considered “high Art” in Islamic cultures.

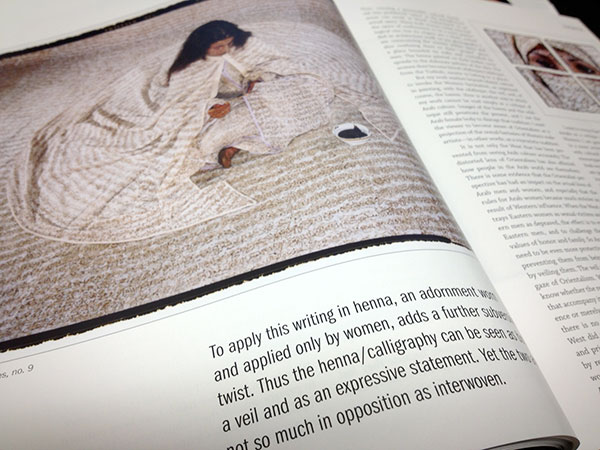

The preparations for the photo shoot start up to six months in advance, writing the fabric that covers the walls, the furniture, and the women’s clothing. I do most of the writing, but for the Converging Territories series, I had help from two women who helped me write the text on the walls, but I did all the writing on the models and their clothing. With Les Femmes du Maroc, which are set in a Boston studio, I do all the writing and it takes more than six months at a time to finish enough fabric to allow for changing the set after each photograph—as the henna dries it flecks down, requiring rewriting each time the women move. (In the photograph above you can see the amount of fabric I used on one day of a photo shoot.)

My work is process oriented, and the quality time I spend making the work is the most important part of being an artist. The process generates new perceptions and facilitates personal transformation, which may help discover new forms of self-expression that are liberating.

April 2013

Lalla A. Essaydi (lallaessaydi.com) grew up in Morocco, attended the École des Beaux-Arts in France, and now lives in the US, where she received an MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Tufts University, in 2003. Her work has been widely exhibited internationally and is represented in a number of collections, including the Williams College Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Fries Museum, and the Kodak Museum of Art. Her exhibition Revisions at the National Museum of African Art (2012–2013) featured thirty multimedia pieces selected from Essaydi’s photographic series.