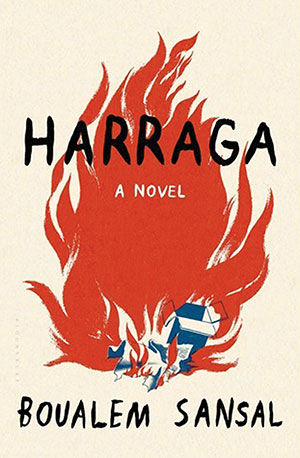

Harraga by Boualem Sansal

Frank Wynne, tr. New York. Bloomsbury. 2015. ISBN 9781620402245

Boualem Sansal dedicates this novel to illegal immigration. The term harraga is an Arabism that literally means “path burners,” which refers to illegal immigrants: thousands of young people who try by all means to leave the misery of their countries and voyage to “the promised land.” Such a topic easily captures the attention of the European and the Maghrebi or African public as both are directly involved. But this paratext must be considered more in its symbolic sense.

Boualem Sansal dedicates this novel to illegal immigration. The term harraga is an Arabism that literally means “path burners,” which refers to illegal immigrants: thousands of young people who try by all means to leave the misery of their countries and voyage to “the promised land.” Such a topic easily captures the attention of the European and the Maghrebi or African public as both are directly involved. But this paratext must be considered more in its symbolic sense.

The story concerns Lamia, the main character and narrator of the story. Living alone in Algiers, Lamia receives an unexpected visit from Chérifa, who will change her life. Arriving from Oran, the girl is “illegitimately” pregnant. She has taken refuge in Algiers under the guidance of Soufuane, Lamia’s brother, who left Algiers to take off illegally to Europe. Lamia has tried in vain to find him with the help of associates that prove powerless. However, Sansal diverts from the plot suggested by the title to tell a different story consistent with another significant dimension of “Harraga.” Indeed, the story revolves around the social and political situation of Algeria, including the confusion of youth. Emigration—which was to be the central concern of the work—becomes secondary and is forced to account for factors that contribute to Algerian misfortune, including its history, which is manifested through the spatial topography of the home and the neighborhood of Ramp-Vallée.

In Harraga, the narrator lives in an old house that holds a significant portion of Algerian history, for which it is a metaphor. With the establishment of the history of the house, Sansal wants to reencounter the original rupture that might explain the present violence. From the description of the house, the author proceeds to that of the neighborhood, which is characterized by disharmony and reveals the intolerance of rulers and bureaucrats who promote all forms of extremism and close all horizons to their victims. It seems that the space, which drives them to dream, represents the transient trace of determining the past and future identity of the characters. The narrator is obsessed with stories and legends surrounding her residence. With the identity acquired in this space, Lamia regains an otherness that will be both her strength and her weakness. She becomes marginal because the weight of history suffocates her. Harraga tells not only the story of illegal immigration but that of exile in its broadest sense, including loneliness.

Latifa Zoulagh

University of Oklahoma