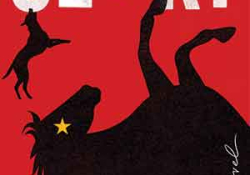

We Need New Names by NoViolet Bulawayo

New York. Reagan Arthur Books / Little, Brown. 2013. ISBN 9780316230810

New York. Reagan Arthur Books / Little, Brown. 2013. ISBN 9780316230810

Written with kinetic energy that crackles with life, NoViolet Bulawayo’s debut novel should be read by anyone interested in emerging voices in world literature. At times joyful, funny, melancholic, ferocious, and defiant, Bulawayo’s first-person narrator, Darling, is a trenchant observer of the human condition. After meeting a wealthy visitor from England near her home in Zimbabwe, a young Darling takes note of the visitor’s “smooth skin that doesn’t even have a scar to show she is a living person.”

Darling is adept at reading people for signs of privilege or privation, camaraderie or confrontation. Whether as a young girl who finds comfort in the company of her friends as they steal guavas and try to avoid the harsh world of adults or as a teenager who, after years living in the United States, has become jaded and cynical, Darling speaks to us with a voice that is direct, powerful, and believable. On the return of her father, ravaged by HIV/AIDS after living in South Africa, Darling says: “Father comes home after many years of forgetting us, of not sending us money, of not loving us, not visiting us, not anything us, and parks in the shack, unable to move, unable to talk properly, unable to anything, vomiting and vomiting.” Bulawayo humanizes personal hardship by avoiding platitudes and letting Darling speak her own truths.

In Zimbabwe, Darling and her friends at times witness violent events. Bulawayo relates such moments and their aftermath in terse and revealing language. Darling describes the games she and her ten-year-old friends play as they run through the city: “Bastard is at the front . . . then myself and Godknows, Stina, Sbho, and finally Chipo, who used to outrun everybody in all of Paradise but not anymore because somebody made her pregnant.” In the United States, Darling is caught between nostalgia and estrangement from the world she has left. About to finish high school, Darling Skypes her mother’s house, only to be confronted by a now-assertive Chipo, who challenges Darling’s authority to speak about Zimbabwe. “What are you doing not in your country right now? Why did you run off to America? Tell me, do you abandon your house because it’s burning or do you find water to put out the fire?” Equally unhappy to be asked about “back there” by Americans who know little about Zimbabwe, Darling develops a cutting perspective on the foibles of Americans. Cleaning the house of a wealthy family, she reads the daughter’s diary and dismisses the “expensive nonsense [written] in her expensive diary.” The father “has traveled all over Africa but all he can even tell you about are the animals and parks he has seen.”

With access to more things, food, and personal liberty than she would have experienced in Zimbabwe, Darling remains unsettled. “In America, roads are like the devil’s hands, like God’s love, reaching all over, just the sad thing is, they won’t really take me home.” As Darling has come to realize, there may no longer be such a thing as home to return to.

Jim Hannan

Le Moyne College