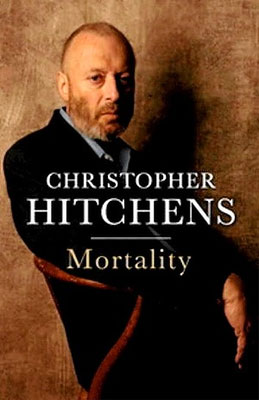

Mortality by Christopher Hitchens

New York. Twelve. 2012. ISBN 9781455502752

The phrase “the year of living dyingly” occurs only once in Christopher Hitchens’s new memoir, Mortality, but it is strong enough to stay with the reader long after the book has concluded. If I’ve learned one thing from this slim tome, it’s that death is easy; it’s dying that takes away our dignity, and with it, our humanity. Mortality is an honest stare-down, sometimes brutally so, in the face of death.

The phrase “the year of living dyingly” occurs only once in Christopher Hitchens’s new memoir, Mortality, but it is strong enough to stay with the reader long after the book has concluded. If I’ve learned one thing from this slim tome, it’s that death is easy; it’s dying that takes away our dignity, and with it, our humanity. Mortality is an honest stare-down, sometimes brutally so, in the face of death.

The seven chapters that make up Mortality are originally from a series of articles Hitchens did for Vanity Fair, a magazine to which he frequently contributed. The eighth chapter constitutes a series of fragments Hitchens was working on when he died. Bookending the memoir is a foreword by Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter, and an afterword by Carol Blue, Hitchens’s widow.

Early on in the memoir, Hitchens declares: “The absorbing fact about being mortally sick is that you spend a good deal of time preparing yourself to die with some modicum of stoicism (and provision for loved ones), while being simultaneously and highly interested in the business of survival.” The fact that Hitchens continued to write up to the very end displays an intense will to go on living, even in the face of death. But perhaps more important, this memoir is further testament to a will to write and think. Life without writing would be unthinkable for Hitchens, as he admits more than once in this book. Where it would be easy to read this memoir as a self-serving deathbed meditation, it’s really a gift to those who have lived with Hitchens and his writing for decades.

In one of the most touching chapters, Hitchens recounts the loss of his voice. In a resonant way, Hitchens saw his voice as a type of weapon. When he began to lose it, he found himself unable to argue and therefore think. In another chapter he describes the way one listens to and thinks of music differently when one has been diagnosed with a terminal disease. He tells about a friend giving him a Leonard Cohen CD and listening to Cohen’s “If It Be Your Will,” but added that it is perhaps best not to listen to this song late at night.

Future generations may read Mortality as only a curious and personal end to an otherwise glorious career as a thinker in an age when society fought hard to reduce thinking to a sound bite. What future generations should take away from this book is the lesson that even in the face of death, Christopher Hitchens never blinked. He never gave in and acknowledged God’s presence in his world. One cannot help but admire a man with convictions like that. The phrase “there are no atheists in foxholes” would never have applied to Hitchens. He was caught in his own foxhole, and when death (or God) called his bluff, he never blinked.

Andrew Martino

Southern New Hampshire University