Home

With Neil Young playing in the background, a New Zealand woman living in Australia recrosses the ocean over a game of Checkers.

Luke shakes the last hand. “If you need to talk,” he says, “just give me a call.” He picks up his alb and walks to the car. In the driver’s seat, he sits staring through the windscreen. Turns on the ignition and drives. Past straggly eucalypts, dry earth colors. A haunting steel-stringed guitar, something Spanish, comes over the radio. A familiar, deep voice: Who by fire, who by water . . .

As he opens the French door, he sees the flickering TV, his stepson sitting on the floor motionless, just the twitch of a finger, thumbs circling, sliding back and forth. He sighs. The boy’s been there ever since he left, and Luke’s had enough death this week without adding electronic carnage.

“You’ve been playing that blasted game all day,” he says. “Why don’t you go and shoot hoops or kick a footy? Or read a book or better still, go and practise the guitar.”

Max looks up from the PlayStation. “But I only just got it—”

“Three days ago.”

“But I’m playing online, I can’t just quit—”

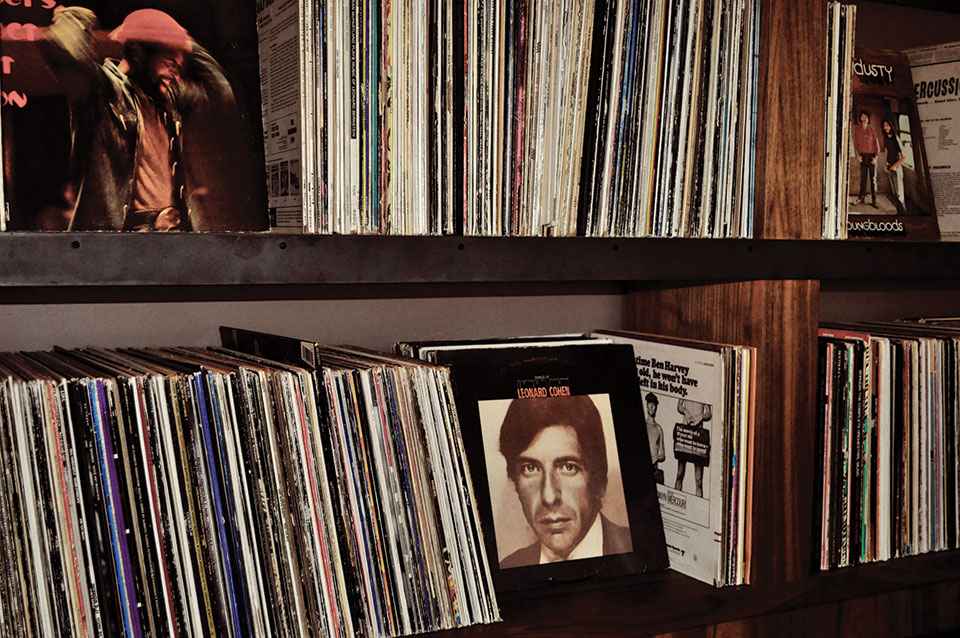

“I tell you what,” Luke says, “I’ll let you carry on. As long as I can play Leonard Cohen as loud as I like. When you turn that blasted game off, I’ll turn off Cohen.”

The boy slumps a little, his face still intent on the screen, still thumbing the controller. “Okay.”

Jess is lying on the bed against plumped up pillows reading Somebody Loves Us All.

“How long do you think he’ll last?” Luke asks.

“Dear Heather” is so loud it could be playing in the same room. She has to smile at her husband’s warped ingenuity but still feels sorry for her son. A friend called Cohen’s songs music to suicide to, though this particular album with Anjani isn’t as familiar. “Three songs? Four at most,” she says. Max is only half-Chinese and she’s not remotely superstitious, but four after all is deadly. Even if he lasts the full album, they have plenty of Cohen: Live in London, Songs from the Road, The Essential, Ten New Songs. . . . And then there’s Neil Young’s Greatest Hits.

“Please,” Max would plead with her, “please—not Neil Young,” but his songs take her back to varsity days, freedom, innocence, the boy two doors down in the hostel playing every Neil and Bob album ever recorded. Road music, Luke calls it. Good for playing loud as they motor down the freeway, especially in Australia where the GPS might say, “Drive 345 kilometres and then turn right.” “Southern Man,” “Comes a Time,” “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” . . . She delights in the melodies, the laid-back beats and guitar riffs, a voice that can somehow carry a tune while sounding like the slow strangulation of a half-wild tom.

Max comes into the room during “Undertow.”

“Hallelujah,” Luke says.

“So can you turn it off before that comes on?” Max says.

“Chinese checkers?” Jess asks.

Max gives her one of his you’ve got to be kidding me looks and slinks off to his room at the back of the house.

“Play your guitar,” Jess yells after him.

“Come on Empress of Checkers,” says Luke. “I’ll give you a thrashing.”

“Yeah right,” she says, sounding like a billboard for Tui beer.

Currawong, wattlebirds, magpie-larks—she’s beginning to warm to the natives here, their sheer numbers and exuberance. Yet when she was last in Wellington she picked up a soft toy in a tourist shop, pressed the button, and listened to the familiar sound. She wishes she’d brought it back even though the silly thing was quite ugly and didn’t look anything like a tui. All over the city, clowning and mimicking, whistling, clucking, and chortling, going crazy with song from the tree in her old backyard. Parson bird, she’d read somewhere. The tuft of white at the throat. She doesn’t like the word parson. It sounds uptight. Un-delicious. Parson’s nose.

But now Leonard’s moved on to “Morning Glory,” talking to himself, endlessly talking to himself, backed by double bass and something like xylophone or glockenspiel. “Are we moving towards some transcendental moment,” he says, voice long fallen into his shiny black shoes. “That’s right,” he says.“That’s—”

Thank God. Luke’s a man of his word, one of the best decisions she’s ever made, and just like that, Leonard’s cut before he can pull off his moment. Jess loves “Suzanne,” “Hallelujah,”“If It Be Your Will” . . . but Glory’s self-talk was starting to get irritating. She puts down her book and goes to the front room. As far from suffering children as any reasonable parent can get. Luke’s already at the table, checkers ready and waiting. “You go first,” she says, wanting to give him half a chance. She puts on a CD and sets the volume low.

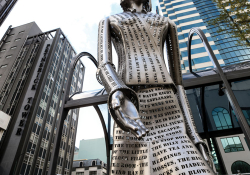

“I wanna live, I wanna give,” she sings as she clacks a checker over the board. “I’ve been to Wellywood, I’ve been to Redwood, I’ve crossed the ocean for a heart of gold . . .”

“Wellywood?” Luke looks up. He’s moved his checker only one place.

“Sweetie,” she says, “New Zealand’s not the place you remember—all sheep and mispronounced Maori place names. We’ve had Lord of the Rings, King Kong.”

She smiles. Her checker skips over and over. As it finds its way home.

Geelong, Australia