“Do What You Love and the Love Will Follow”: The 2023 NSK Prize Lecture

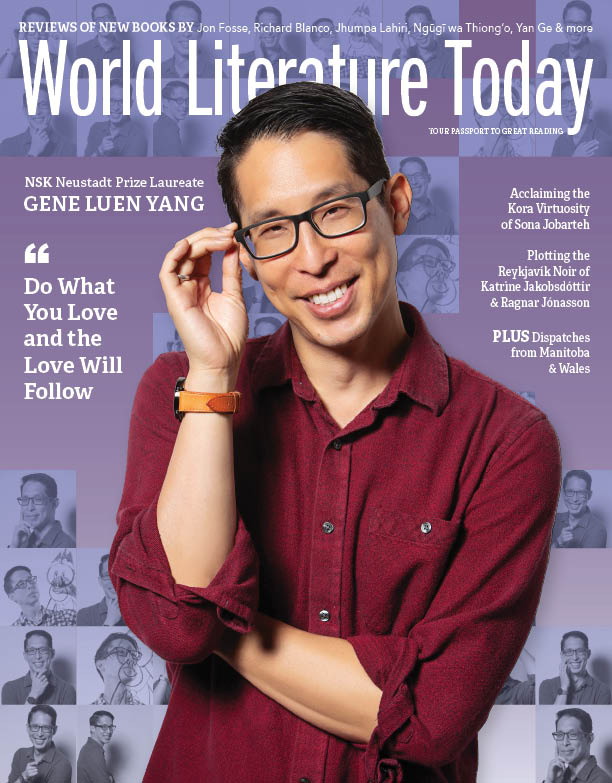

After accepting the NSK silver medallion, certificate, and a check symbolizing the $35,000 award, Gene Luen Yang delivered a heartwarming story about the arc of his career, making art with friends, and the earned wisdom of what creating comics has taught him.

THERE ARE SO MANY PEOPLE TO THANK:

God, for both the blessings and the trials.

My wife, Theresa, who is not a comic book person but supports my love of comic books anyway.

My kids, who love comics but not as much as me.

All the people responsible for the Neustadt Lit Fest. Nancy, Kathy, Sam, the entire Neustadt family, RC, Terri, Daniel, Kay, Parker, and everyone else. It has been such a pleasure getting to know you all these past few days.

Trung Lê Nguyễn, not just for nominating me for the prize, but also for being one of the brightest new stars in the American comics scene.

My agent, Judy Hansen, for two decades’ worth of wisdom and advice.

My editor Mark Siegel and First Second Books. I’m so grateful for the home for cartoonists that you’ve created.

All the other publishers I’ve worked with: Dark Horse Comics, DC Comics, and Marvel.

Teachers, librarians, bookstore owners, and comic shop retailers. Without you, storytellers like me would not be able to do what we do.

And finally, our readers. Thank you for choosing to spend time with our stories.

I became a comic book nerd when I was in the fifth grade. Before that I was just a run-of-the-mill nerd, no modifier. When I was a kid, every local bookstore had what was called a spinner rack. This was a wire frame rack that would sit in the corner of the store. It would carry a month’s worth of comics. The whole thing would spin so you could see all the comics. One night, my mom took me to our local bookstore and bought me a comic book from that spinner rack: DC Comics Presents #57 starring Superman and the Atomic Knights. I brought it home and read it, and by the time I got to the last page, I was in love.

By the time I got to the last page of DC Comics Presents #57, I was in love.

When I found out there was something called a comic shop, a store full of nothing but comic books, I was astounded. Every weekend, I begged my mom to take me. Occasionally, she relented.

When I got my driver’s license at age sixteen, I drove straight to my local comic shop. Not my girlfriend’s house; my comic shop. Back then, Friday was New Comic Book Day. For the uninitiated, New Comic Book Day is the day of the week that comic shops get their shipment from the distributor. Nowadays, it’s Wednesday (or Tuesday for DC Comics) but back in the 1980s and ’90s, it was Friday. Throughout high school, my good friend Jason, my younger brother Jon, and I had a ritual. Every Friday, we’d pile into Jason’s Volvo station wagon and go to our local comic shop. That might’ve been my most regular habit while I was in high school.

I’d bring home a stack of comic books. I’d spend hours reading them, then carefully put each issue into a clear plastic sleeve with a cardboard back. I’d use a small strip of scotch tape to secure the plastic sleeve’s flap and store them in alphabetical order in a long box. I had several of these long boxes in my closet. My room was almost always a mess. I had clothes and schoolbooks and mixtapes everywhere, but my long box was never a mess. That long box might’ve been the most organized part of my life while I was in high school.

Now, my dad watched me do all this and he was pretty disgusted. I am the son of two immigrants. My mom was born in mainland China and my dad in Taiwan. They came to the United States for graduate school, met, fell in love, got married, and had me. To be fair, my mom had artistic inclinations herself, so she was always more understanding of my love for comics. My dad, however, is about as stereotypical of an immigrant father as you can find. He’s very practical-minded. He was constantly worried about how I was going to make money and feed myself as an adult. He and I butted heads over my future all the time.

Right before I went off college, my dad sat me down. He said, “Gene, you have to major in something practical.” And by practical, he meant doctor, lawyer, or engineer. He said, “If you do that, if you get a degree in something practical, you can do whatever you want, make whatever life choices you want, and I promise I won’t say anything. I just want you to have that degree.”

So I got that degree. I went to college and majored in computer science. That degree wasn’t entirely for my dad because I really did enjoy coding when I was a kid. It was maybe 80 percent for my dad.

After graduation, I took a job as a computer programmer at a small software company in Emeryville, California. I stayed there for two years, and my dad kept his promise. He didn’t say anything.

Then I went on a silent retreat for five days in the Santa Cruz mountains. The only person I talked to was the priest who served as the retreat’s spiritual director, and even then it was only for an hour a day. By the time it was over, I had arrived at two decisions. First, I was going to become a high school teacher. Second, I was going to get serious about making comic books.

I quit my computer programming job and found a position as a computer science teacher at Bishop O’Dowd High School in Oakland, California. Then, during my off time—summers, winter breaks, and after work—I wrote and drew my own comics.

My dad watched me do this, and he kept his promise. He didn’t say anything. But every few months, I would get an envelope in the mail from him. There wouldn’t be a letter in the envelope or anything, just newspaper clippings: want ads from Apple or job listings from Google or articles that compared teacher salaries to computer programmer salaries. Every few months, I would get one of these envelopes. I mostly ignored them.

But to be honest, especially from the vantage point of now being a father myself, it’s not like my dad didn’t have a point. Teachers don’t make a lot of money, especially when you compare them to technology workers. And in the ’90s, it was almost impossible to make money at comics.

Many people don’t remember this, but the ’90s was a very difficult decade for the American comic book industry. These days Marvel is a pop culture juggernaut. Back in the ’90s, though, Marvel declared bankruptcy. Some people were even predicting that the company would go completely under. Because of Marvel’s importance to the market, if Marvel died, it would take almost all the comic shops in America along with it. The entire industry was on the brink of extinction.

I used to go to comic conventions, and it wasn’t like how it is now. These days, you have to purchase your tickets months in advance, and it’s a frenzy to get them. Back then, you could buy them at the door, same day. I remember being at my very first San Diego Comic-Con, the biggest comic convention in America, and on Sunday it felt like there were more exhibitors in the exhibit hall than attendees. You could almost see tumbleweeds going through the aisles.

At these conventions, I’d attend panels and listen to my favorite artists, writers, and editors—creators I’d admired since I was in the fifth grade—talk about how we were about to see the death of the American comic book. Many of my favorite artists were illustrating for video-game magazines just to make ends meet.

I realized that I would probably never be able to make a living at comics, but I still loved them. I decided to become a comics self-publisher.

Here’s how it worked. I would write and draw a comic book. I would take it to my local Kinko’s to run off copies. I’d staple the copies into books and then sell them at comic conventions. There were a handful of conventions that focused on minicomics: handmade, xeroxed comics. There was one called the Alternative Press Expo on the West Coast and another one called Small Press Expo on the East Coast.

Through these conventions, I met people who loved comics as much as I did, who weren’t in it for the money, who didn’t care that the American comic book industry was falling apart. We made and sold and traded minicomics, not because we were trying to make a living at them, but simply because we loved the art form and wanted to keep it alive.

A new ritual grew out of this community. Throughout my twenties, a group of cartoonists in the Bay Area would get together once a week at somebody’s apartment. We would have dinner together, then write and draw and talk shop. We’d look at each other’s work and give feedback. We would trade tips about pens and paper. We would give each other reading recommendations. I never went to art school, so I consider this period of my life as my art school. We called ourselves Art Night.

This was the late 1990s and early 2000s. It was an incredibly fulfilling time for me. I was working as a high school teacher, a job that I really loved. And on the side, I was making comics as a part of this community of young cartoonists.

In the year 2000, I began working on a project that had been on my heart for a while. By this point, I’d been making comics for about five years. I’d always had Asian American protagonists, but their Asian American-ness was never a part of the story. Because my own cultural heritage was such an important part of how I found my place in the world, I wanted to do some kind of story where that was the focus.

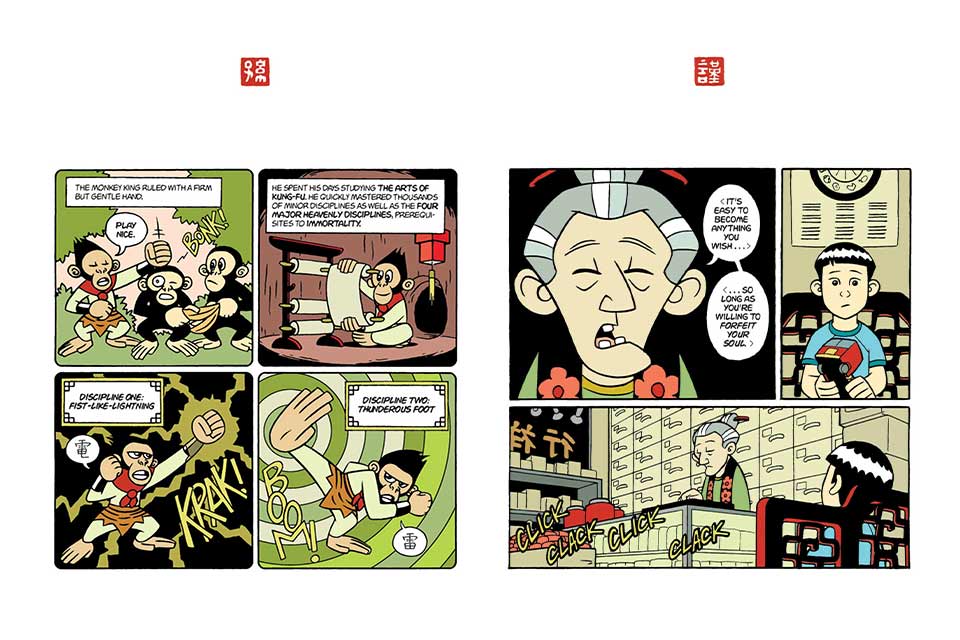

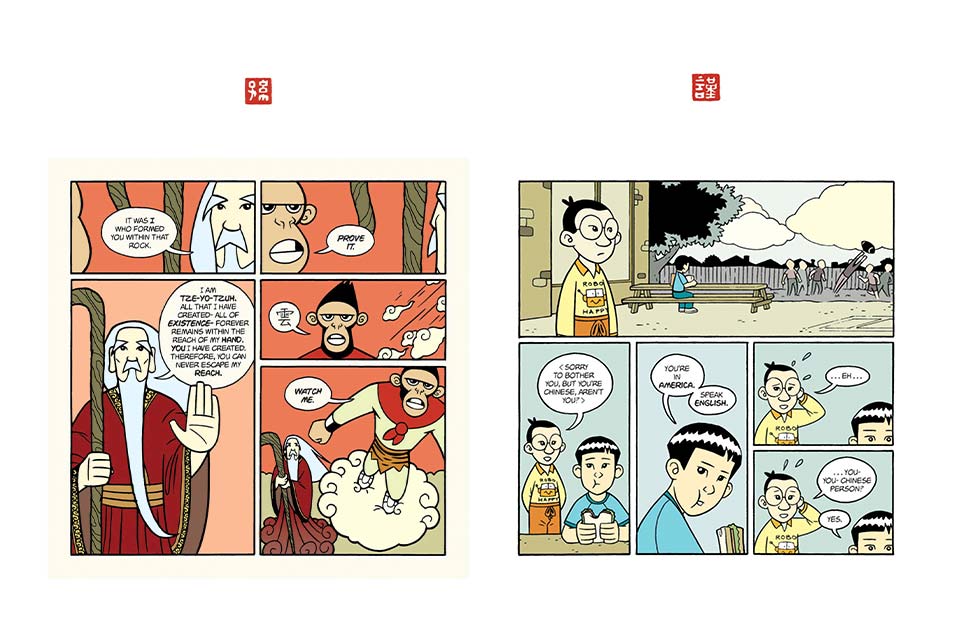

I began writing and drawing a story called American Born Chinese that I published as a xeroxed minicomic.

While I was doing all this, something was happening in the wider American comic book industry. First, in 2003, two graphic novels hit the New York Times bestsellers list. One was Persepolis, which is now regarded as a classic graphic novel. It’s the autobiography of an Iranian French cartoonist named Marjane Satrapi. The other was In the Shadow of No Towers, by Art Spiegelman, an account of his experience in New York City during 9/11.

Two graphic novels on the bestsellers list was a shock. Before this, nobody thought a comic book or a graphic novel—which is essentially a comic book thick enough to need a square binding—could ever sell that well. Soon, everybody was talking about graphic novels, and traditional book publishers began coming into our world, the world of self-published comics, looking for the next New York Times bestseller.

One of the cartoonists they approached was Derek Kirk Kim, one of my good friends from Art Night.

Around 2004 or 2005, I was getting close to finishing American Born Chinese. Derek introduced me to Mark Siegel, the editorial director of First Second Books, Macmillan’s brand-new graphic novel imprint. Mark had been courting Derek, wanting to publish his next graphic novel. (Derek has since done multiple works with First Second, the most well-known of which is probably Same Difference, a brilliant book.)

Derek sent American Born Chinese to Mark, and Mark liked it enough to offer me a contract. First Second Books published American Born Chinese in 2006. It was colored by Lark Pien, another one of my Art Night friends.

The response to American Born Chinese was well beyond anything I could have imagined. Librarians, teachers, bookstore owners, comic book fans, and even judges for prizes came out and supported the book. I was shocked.

American Born Chinese marked a turning point for me in many different ways, but the one that mattered most to my father was money. Before, I would lose money every time I put out a comic book. Now, I was actually making money.

Just a few months after it was published, American Born Chinese was nominated for a National Book Award. A couple of newspapers wanted to do articles about me and the book. One was the San Francisco Chronicle. Their reporter called me to make an appointment. Then one afternoon, they met me after I finished my day at Bishop O’Dowd High School, and we sat down for an interview.

The other newspaper was the World Journal, a Chinese-language newspaper for overseas Chinese. Their reporter did not call to make an appointment. She just showed up at my classroom like she was my auntie. Luckily, we were having a lab day that day, so my students were all busy working on a coding project while I sat down to talk with her.

Even though the interview began a little awkwardly, I was deeply thankful to the World Journal for doing a feature about me. A few weeks later, I visited my dad. He showed me that he had that World Journal article clipped out and preserved in a plastic sleeve. That was when the envelopes of newspaper clippings stopped.

When I was in the fifth grade, I never could’ve dreamed that my life would be like it is now. I’ve gotten to publish multiple books with First Second. I’ve gotten to work on the graphic novel continuation of a popular Nickelodeon show called Avatar: The Last Airbender. I’ve gotten to work in both the DC Universe and the Marvel Universe.

And this past May, American Born Chinese was adapted into a television show on Disney+, starring two Oscar winners, Michelle Yeoh and Ke Huy Quan. Sometimes, it feels like I’m living someone else’s life.

I told you earlier that my dad has always been worried about how I would make money. There’s an old adage that goes, “Do what you love and the money will follow.” It describes what happened to me, doesn’t it? I did what I loved, and, eventually, the money followed.

I don’t think, “Do what you love and the money will follow” is a hard-and-fast rule of the universe.

But my wife and I have four kids, ages eleven to twenty. I’ve thought long and hard about this adage, about what I want to teach my kids about the relationship between love and money.

The hard truth is I was lucky. I was extremely, extremely lucky. I don’t think, “Do what you love and the money will follow” is a hard-and-fast rule of the universe. If I’d gotten hit by a bus at the age of thirty-six, a month before American Born Chinese was published, I would’ve done what I loved for ten years, and the money would not have followed.

Like I said, I’ve thought long and hard about this, and I think a better adage might be this:

Do what you love and the love will follow.

Let me explain.

First, by making comic books, I gained a much deeper appreciation of the medium of comics. Now when I read comic books and graphic novels, that experience is richer.

When you learn to practice an art form, it deepens your appreciation for it.

This is why it’s important to teach our children how to write and paint and make music even if they don’t ever want to be professional authors or artists or musicians. When you learn to practice an art form, it deepens your appreciation for it, which in turn deepens your appreciation for human expression.

By doing what I love, I deepened my love for comics, and maybe my love for art in general.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, I met some of my closest friends through comics. We’ve been friends for decades now. Our friendship began because of a shared love of comics, but life throws a lot of difficulty at you. You get your heart broken. People you love get sick and die. You go through all sorts of failures and hardships. Having friends by your side through the hard parts of life, especially friends who’ve known you since you were young, is a blessing. It goes beyond comics.

By doing what I love, I found love—specifically, the love of friends.

Here’s what I would submit to you. Pursue what you love with passion. You might eventually make a living at it. That is definitely a possibility, but it’s also not the point. Even before that possibility realizes itself, know that your pursuit is not in vain. By doing what you love, you’ll gain a deeper appreciation of not just a particular art form but of the world of art as a whole. By doing what you love, you’ll find yourself traveling alongside people who share your love, people who have the potential to become lifelong friends.

And I believe that is actually a hard-and-fast rule of the universe:

Do what you love and the love will follow.

Norman, Oklahoma

October 25, 2023

Read more about Gene Luen Yang