Editor’s Note

Some days light is the color of all / my losses.

—Lauren Camp, “Alma’s Stripes”

Do poems have dimensions? We know they occupy space on the page, but can we measure verse the way we measure construction materials or works of art? Visit a hardware store, or walk through a museum, and the seemingly infinite expansion of the imagination is soon boxed into parcels of length x width x height. Read a book, and you immediately enter a world of constraints—the linearity of print, the consecution of pages, the terminus of the cover.

Do poems have dimensions? We know they occupy space on the page, but can we measure verse the way we measure construction materials or works of art? Visit a hardware store, or walk through a museum, and the seemingly infinite expansion of the imagination is soon boxed into parcels of length x width x height. Read a book, and you immediately enter a world of constraints—the linearity of print, the consecution of pages, the terminus of the cover.

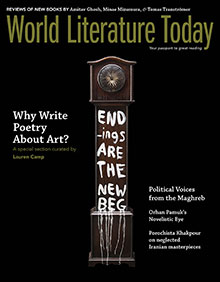

Of course, no creation exists in a space independent of the world at large. Just as the self-containment of a book is vulnerable to elements beyond the covers that would rush in to engulf the words, the writer’s conceit of stopping or transcending time is as old as Homer’s description of the shield of Achilles and Dickinson’s “Because I could not stop for death.” In this issue’s cover feature devoted to poetry inspired by post-1950 visual art (page 35), thirteen international poets fashion word-pictures that attempt not only to verbalize a visual analogue but to liberate moments of stasis from the prison-house of space. With each poem, you’ll find reproductions of the art that inspired it, allowing readers to witness the acts of transposition first-hand.

As their point of departure, the twenty poems included in the section describe mostly paintings—oil, acrylic, gouache, or watercolor on canvas, board, masonite, wood, paper, cardboard, etc.—but also faded black-and-white photos from a family album and etched gourds. Several of the painters who inspired the poets have work in major art museums—Salvador Dalí, Elizabeth Murray, Remedios Varo, among others—yet some of the artists are relatively unknown. The majority of the poems featured are translations from other languages—Arabic, French, and Spanish—and all are published here for the first time in English.

In her essay “How Ekphrasis Makes Art” (2011), Cole Swensen writes: “Ekphrasis that makes an object or scene out in the world into a work of art allows the reader to be present at the precise moment that art is made, at the instant of the shift from presence to representation, when something slips from the perils of time into the distilled space in which it can come to mean more than itself” (Noise That Stays Noise). Nevertheless, the work of Australian artist Fiona Hall, whose art appears on the cover and inside the issue (pages 35 and 46), is all about the “perils of time.” As part of the 2015 Venice Biennale, Hall’s series entitled Wrong Way Time stages time’s dark ravages in the heart of human existence. The installation includes eight longcase clocks, eighteen cuckoo clocks, twelve mantle clocks, a banjo clock, recordings of crows, and an alarm clock set into volumes of the British Museum’s General Catalogue of Printed Books. Using the clock cases as her canvas and enamel and oil paint as her medium, Hall paints graffiti-like watchwords and numbers, the names of nuclear meltdowns, nooses, skeletons, skulls, tally marks, and barbed wire directly on the clocks. As Linda Michael writes in her lead essay for the exhibition catalog, the longcase clocks function as “memorial totems” and remind her of standing coffins. “Curiously,” she writes, “clocks have no zero, so keep the ultimate end at bay.”

In their own way, too, the shapes of ekphrastic poems resemble two-dimensional coffins, even as they exist—like the visual art they interpret—in a “distilled space [that] can come to mean more than itself,” in Swensen’s words. Here, such distillations remind us that, although narrative is traditionally given pre-eminence as the temporal art par excellence, a poem not only imprints a still life on the page but is also, in the time we take to read or listen to it, haunted by a clock always ticking in the background. Guest editor Lauren Camp asks, “Why write poetry about art?” For each of the poets featured here, the “ultimate end” is the poem itself.

Daniel Simon

Special thanks to Lauren Camp for her brilliant work guest-editing this issue’s cover feature and to the Australia Council for the Arts for facilitating the art by Fiona Hall.