A Buenos Aires Affair

In any discussion of Buenos Aires, it’s probably useful to start out by defining our parameters. For the rest of the world, “Buenos Aires” conjures images of tango dancers strutting their stuff on the sidewalk, football stadia garlanded with light blue-and-white ticker tape, or a pink palace with an iconic balcony. Argentinians, however, tend to use “Buenos Aires” to refer to the huge, politically nonsensical province that surrounds the actual city, which is known as “Capital Federal” or “CABA,” the Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires—if someone living in the city says they live in Buenos Aires, you can be sure they’re a foreigner, not a true porteño, as its denizens are known.

The fact is that the city spills out over the rather arbitrary boundary of the General Paz freeway for miles in every direction, other than toward the river (itself so vast that most visitors would mistake it for a sea or bay), and every day millions of people commute in and back for work, study, leisure, and myriad other reasons. In addition to transcending its boundaries physically, in political, economic, and cultural terms the city’s influence spans the entire country, for better or worse; to offer an example, you can be having breakfast in a café a thousand miles away in Jujuy, but the news bulletins blaring on the TV overhead will still be reporting on the traffic on the General Paz. In Argentina, all roads lead—quite literally—to Buenos Aires.

In Argentina, all roads lead—quite literally—to Buenos Aires.

For the purposes of this cover feature, however, we’re taking a necessarily narrower focus to concentrate on the city proper—and even then we’re really doing little more than scratching the surface. After all, the city is made up of forty-eight official barrios, or neighborhoods (plus several unofficial ones depending on whom you talk to), and each has its own history, stories, and, in many cases, its own bona fide identity—see, for instance, Julia Kornberg’s wonderful piece on the Once neighborhood (not, by the way, an official barrio). Rather than a totality, what we hope the texts in this issue convey is something akin to the authentic sensation of spending time in Buenos Aires. Having lived in the city for over a decade, I’ve always found it to be a curiously nebulous experience, difficult to put your finger on in a way quite different from other cities across the world. My sense is of identities, ownerships, and meanings still being vigorously negotiated, when not fought over outright. Head into the so-called centro (the location of the actual geographic center of the city is debatable), and you’ll find plenty of patrician, Haussmannian architecture and urban planning, which reflected the confidence of early twentieth-century porteños that Argentina was and would remain one of the great powers. Turn the corner, though, and you’ll find yourself at the entrance to one of the city’s largest shantytowns, of which, sadly, there are dozens. Here, economic migrants have, with remarkable ingenuity and fortitude, built up their own improvised architecture based around breeze blocks, corrugated iron, and precarious, not-very-legal connections to the city’s utilities.

In Buenos Aires, grandeur and destitution are only ever a few steps away from each other, a reflection of rather more turbulence and tragedy across the twentieth and nowtwenty-first centuries than those optimistic late Victorian builders would likely have anticipated. Contrast is a major part of the Buenos Aires experience, but not always in the stark terms described above. Personally, I’m always struck by the variety of different building styles one sees on any given street across the city: a faux-Swiss chalet might sit next to something vaguely modernist, which will in turn be neighbored by the deceptively narrow façade of a traditional casa chorizo. The streets are paved with absolutely no uniformity whatsoever; asphalt in varying states of repair gives way to cobbles seemingly at random, while the sidewalks are similarly a patchwork of, one suspects, whatever material happened to be cheap at the time. The planting is just as eclectic but more exuberant still: European-style avenues of lime trees are joined by lush jacarandas, lapachos, and bulbously baroque palo borrachos (literally “drunken sticks,” and boy do they look drunk). And the shade is extremely welcome in summertime, as are the numerous parks.

Buenos Aires is its streets, warts and all.

Buenos Aires has a number of excellent museums, interesting landmarks, and an extremely rich cultural life, but I usually say to visitors that the best thing to do to really get to know the city is to go out for a wander—you’re unlikely to come back without an interesting observation or two. Maybe you’ll wonder at the cultural acceptability of having your pedigree dog—usually of a breed wholly unsuited for the climate—taken out in a pack of twenty or more by harried-looking walkers (no, they don’t pick up after themselves), or the half-naked man with the enormous potbelly looking to make a buck from a barbecue improvised from an old oil barrel, or a cartonero pulling around a large cart filled (and then some) with cardboard and anything else that might have some value at the end of the day. It’s not always pretty, but it’s undoubtedly vibrant—Buenos Aires is its streets, warts and all. Maybe, if you’ve headed into the center, you’ll be struck by the demonstration, replete with banners and drums, parading down the middle of a large thoroughfare. You might think that you’ve stumbled onto a momentous event until you come back the next day to find a similar spectacle, albeit with different colored and lettered banners. Demonstrations, and political expression in general, are as much a part of city life as the traffic jams of which they can also be the cause. This seems important to note right now, given the apparent determination of the recently elected administration to curtail these rights while also cruelly cutting public spending on social programs. With the poverty rate across Argentina now at well above 50 percent, further turbulence seems inevitable, and you can be sure it’ll play out on the streets.

Demonstrations, and political expression in general, are as much a part of city life as the traffic jams of which they can also be the cause.

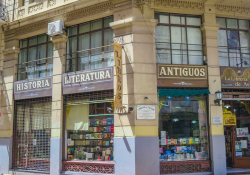

The primacy of public life (or, maybe more accurately, life in public) in Buenos Aires, and its literary implications, is perhaps the overarching theme of the texts gathered here: Leila Guerriero remembers the shock and fascination of coming to the big city; Matías Serra Bradford’s elegy to the bookshops of the city reminds us why Borges thought it so appropriate to locate the Aleph in one of the city’s mysterious basements; Ana Ojeda takes us on a wild bike ride through the city’s streets; Oliverio Coelho shares his love of another major cultural and familial pastime, going to watch football; Cecilia Pavón mines one of the city’s quintessential pleasures, sitting in cafés, for inspiration; Julia Kornberg’s tour of Once shows how richly meaningful (and frustratingly problematic) even simple errands can be in this city; Liliana Viola tells the story of the city’s now-massive Pride parade; Daniel Tunnard remembers his experience exploring one of Buenos Aires’s most cherished institutions, the extraordinarily comprehensive and colorful twenty-four-hour public bus service; and Matías Capelli’s own two-wheeled journey is more contemplative but just as evocative (and also pretty much passes my old house).

Each writer in their own way captures a compelling aspect of life in Buenos Aires. We hope that by the end readers will feel they’ve had a taste of what this wonderful, infuriating city has to offer.

Buenos Aires