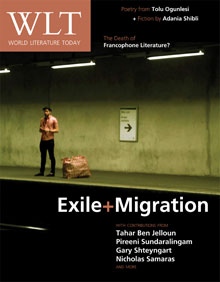

March 2009 WLT

Poet, playwright, and neuroscientist Pireeni Sundaralingam considers how migration defines a person’s identity and art’s ability to build bridges and break down the fears that lead to demonizing others. I heard her read at the PEN World Voices Festival in New York City in May 2008, and our conversation over lunch led to the following e-mail interview.

Michelle Johnson In addition to being published in several leading journals and in college textbooks, your work has been featured in the Barbican Theatre in London, the United Nations Headquarters, the International Museum of Women, and on national radio in Sweden, Ireland, and the United States. You must be touching upon some universal themes. What are they?

Pireeni Sundaralingam My writing describes my experiences living in different countries, and my experience of war, but beyond this, I think that people are interested in reading about how one person might attempt to cross a cultural divide. We live in an era in which community is, increasingly, something that we need to create for ourselves rather than something into which we are born. As a result, I think there is a great hunger to discover how others have walked between worlds. In a way, the specifics of those worlds become less important than the way in which the traveler has attempted to bridge them. And with the growing number of people who are migrants (the United Nations estimates that one in five people on the planet have been displaced), the experience of migration itself—rather than the details of the home country or culture—becomes something that defines a person’s identity.

MJ You and your husband, violinist and composer Colm Ó Riain, produced a CD that features several performers bringing together music and spoken-word poetry. Can you tell us about the project and how it began?

PS Over the last few years, Colm and I have enjoyed trying to find ways to compose poetry and music in a way that doesn’t either compromise the integrity of the poetic phrasing or confine the music to some kind of aural wallpaper. Part of our motivation in creating this album was to commission other poets and musicians to do the same, to invite them to venture into the vast middle ground that lies between songs with catchy tunes but inane lyrics, at one extreme, and poetry spoken with randomly improvised music behind it at the other. We wanted to see what would happen if we took master artists from the fields of poetry and music and encouraged them to collaborate as equal partners.

The second part of our motivation for this project was political. In the aftermath of 9/11, the culture of fear and reprisal led to an escalation of attacks on minority ethnic groups, even here in San Francisco. We were disturbed to see minority communities withdrawing into themselves. It wasn’t simply the fear of physical violence; there was also a sense that, overnight, their contribution to American life had been downgraded, and that they had become second-class—if not invisible—citizens. Colm and I produced this album to counter that climate of domestic “terror” and to celebrate the cultural diversity of the United States instead.

We called the album Bridge Across the Blue, and each one of its eleven tracks brings together musicians and poets to tell the forgotten immigration histories of America. Every track on the album has such pairings, Filipinos with Romani, Native Americans with Gaelic singers, to mention just a few. In each case, we challenged artists to work together with those from other ethnic communities to find common links between their experiences, to build a bridge across their blues. We hoped to create a common vision of political and cultural community, and thanks to the Potrero Nuevo Fund Prize for Social Justice in the Arts, we were able to commission poets and musicians to compose pieces that would do just that.

MS Themes of migration resonate in the CD, your poetry, and your play. Do you have an overall artistic project, focusing on migration, that connects your work?

PS I don’t think of myself as having a specific artistic agenda, other than to write what I know or what I’m trying to explore. Working on the CD was a little different from how I approach the rest of my writing, since I had a specific vision of the end point, in that particular case. In contrast, I usually write in order to discover what lies at the end; it’s my way of trying to understand something. The writing process, for me, typically starts when I’m struck by a pattern of words, or a curious image, and then all I can do is hope that I’ll have the stamina to keep writing until the end emerges. I write simply to construct some kind of meaning from the flotsam and jetsam of life around me.

I’m curious about many things and so this tends to creep into my poetry (my last two poems were, respectively, about a Catholic priest in a retirement home and the hardware tools that my mother uses in her flower-arranging). However, like most people, I’ve been shaped by the countries in which I’ve lived and the people I’ve known. Consequently, the experiences of war, racism, and dislocation permeate much of my writing. I don’t choose to be political in my poetry; I write simply to make sense of the world around me. However, when lives that are similar to mine have been erased by silence, then such personal creative writing takes on a political dimension. Simply writing the “I” becomes political.

MJ The Word and Violin website says you are a cognitive scientist. How has being a scientist informed your writing?

PS Working as a cognitive scientist has allowed me to preserve a sense of wonder about the world around me. It’s a privilege to be engaged in a field in which we are still asking the most basic and yet the most profound questions: How do we acquire language? How do linguistic categories shape our perception? What mathematical patterns has our brain evolved to detect? My chosen disciplines of poetry and cognitive science both allow me to wake up each morning and look at the world as if for the first time, to take nothing for granted.

MJ If you could bring together neuroscience and art in a new way, what would it be?

PS I worry that, for a lot of people, the role of art in sustaining a healthy, functioning society has fallen by the wayside. It is certainly treated as an optional extra in school curricula here in the States. I hope that my future scientific work might, in part, help to revisit these assumptions in a more objective way, and yield a better understanding of how various artistic forms may, or may not, affect day-to-day cognitive functioning.

MJ Yusef Komunyakaa wrote that the speakers in your poetry “are troubled, a long ways from cultural homes and loved ones, but they always have an unflinching ability to forgive and celebrate human possibility. They move on and endure, but they never forget personal histories.” Is this a representation of what you have observed in other migrants? Is it a description of your own outlook?

PS The experience of migration shapes a whole kaleidoscope of lives and coping strategies; I don’t think that these have really been charted fully, either in literature or sociology. I couldn’t claim to be able to even begin to do this justice. However, as regards the subset of lives that I do write about, I’d say that most of my characters are caught in a particular time and place, without being able to see to the other side. It’s that sense of the juxtaposition between different realities, the difficulty of simultaneously embracing different worlds, that keeps drawing me back to write about it.

MJ In the description of your play, War Harvest, you write that “one of the tragedies of the Sri Lankan war is that the rates of suicide and domestic violence among those who have escaped the country are among the highest in the world. This play examines the impact of war on those who survive, exploring the manner in which love, loyalty, and language become fragmented, and the way in which survivors end up clinging to (often quite contradictory) codes of honor.” What are the contradictory codes of honor you explore?

PS The play is an attempt to explore the inherent contradictions in society, by seeing how these are played out within the high- pressure scenarios of immigrant life. It’s about the struggle between the conscience of the individual versus that of the group, something that is even more bitter against a background of unfolding genocide. While one sister in the play appears to reject the traditions of Sri Lankan culture, her loyalty to her family ties her to wanting to change their lives, in addition to her own, while the sister who is culturally more conservative becomes subsumed within a nationalistic cause that, paradoxically, dictates a much more radical upending of societal structures.

MJ You ask these two questions in your play description: “Can there ever be trust across racial boundaries? What makes people cling to the idea of racial purity and fear miscegenation?” Based on your experiences, what are the answers?

PS When I was in the City Museum in Zagreb, Croatia, in 2003, one exhibit caught my attention in particular. It included a black-and-white print from a previous century that claimed to portray the differences between Serbs and Croats: one as a fair-haired, elegant cavalryman and the other as a brooding, near-simian hulk on foot. It would be comforting to think that these are just historical artifacts, but there were similar posters distributed in public spaces in Sri Lanka, not so long ago, aiming to depict the distinguishing physical characteristics of the enemy. Of course, such depictions have little to do with reality, but they speak to a universal need to demonize the “Other,” something that becomes even more heightened during conflicts.

The myth of racial purity is something that has penetrated the histories of most countries at a very profound level. I think it’s an inevitable extension, in social and biological terms, of establishing the finite physical borders of our nation states: first we define our boundaries with barbed wire, and when geography’s not enough, we turn on each other with pseudogenetics.

As for establishing trust across these divides, I still believe that this is possible. I think that so many of our fears are based on a failure of imagination, of getting stuck seeing things through a limited perspective, without considering an alternative. We swallow the myth of racial purity because contemplating complexity, even when the physical evidence is all around us in plain view, is simply too daunting. We are constantly looking for the world to be parsed into heroes and villains; by demarcating the evil of the other, we absolve ourselves of our own failings.

MJ Does art play a role in establishing trust and breaking through fear?

PS I feel that, like so many other human devices, art can be a double-edged sword. It can be used to promulgate disturbing political fictions, like the posters I mentioned, or it can be used to challenge the status quo, to make that leap of imagination that transcends the boundaries of quotidian thinking. Perhaps the most exciting service art can provide our communities is in helping us to see through the eyes of others, despite our own fears.

MJ At the PEN conference, you spoke of the experience of people meeting in exile, which you capture in your poem “Language Like Birds” (see previous page). In the poem, language is both a common bond (trust) and an instrument of violence (fear). Could you talk about that experience and the poem?

PS The poem touches on a recurring experience: that of catching sight of a stranger, on a crowded street, of wanting to approach her because she looks like she might be Sri Lankan, only to find that language can be treacherous. The simplicity of small talk—asking someone’s name, where she lived in Sri Lanka, when she left—becomes fraught with political meaning against the backdrop of an ethnic civil war because the answers inevitably reveal ethnicity, possible political allegiances, perhaps even the history of your family and the nature of your leaving. Asking such basic questions may only serve to conjure up the ghosts of a troubled past, and when so many Sri Lankans have arrived in the West as illegal immigrants, the sudden questions of a stranger can be terrifying. And so, you find yourself on a busy city street, wanting to reach out to someone who reminds you of people you once knew, someone who is probably looking at you with the same questions in her eyes, and finding that war continues to hold both of you as prisoners of silence.

Sadly, this experience is not one that is unique to Sri Lankans. Time and again, I’ve been approached after a reading, whether in Connecticut or Stockholm, by audience members from other war-torn countries (Cambodia, Kosovo, Vietnam, to name just a few) and been told that what I’ve described holds true in their communities as well.

MJ What are you working on now?

PS Aside from a handful of scientific research papers on human perceptual and attentional processes, I’m finishing up my first collection of poems, most of which are based on my experiences in Sri Lanka. My other main project, at the moment, is an article, cowritten with Robert Hass, on the intersection between poetry and cognitive science. We’re hoping to discuss the important cognitive functions that reading and writing poetry serves, from focusing attention to enhancing the ease with which people can shift between different representations. In a sense, poetry serves as the perfect mental gym.

December 2008

Born and raised in Sri Lanka, Pireeni Sundaralingam is a PEN USA Rosenthal Fellow and editor of Writing the Lines of Our Hands, the first anthology of South Asian American poetry (forthcoming). Her poetry has appeared in newspapers, magazines, university texts, and anthologies. She has given readings on national radio in several countries, and her work has been featured at the United Nations. Also a cognitive scientist, Sundaralingam is interested in the confluence of science and art. She and husband, Colm Ó Riain, perform together as Word & Violin (www.wordandviolin.com) and coproduced the CD Bridge Across the Blue, featuring poets and musicians collaborating on what About.com called “one of the top ten albums of poetry and music ever recorded.” Educated at Oxford, Sundaralingam now lives in San Francisco.