Celebrating the Tribes and Species of the World and the Radiant Symmetries That Join Us

Curating an exhibit for the Central Park Zoo, a poet and her collaborators create a celebration of our connection to the physical world, using the work of poets who strive to sustain that world.

A Chicago mother carries her son from one oxygen tent to another. The boy becomes a man who loves spiders. His screensaver frames a precise nineteenth-century lithograph of arachnids from German biologist Ernst Haeckel’s Art Forms in Nature.

I meet this lover of spiders, survivor of oxygen tents, for the first time in a studio in New Orleans on Dauphine Street where Audubon lived and painted Birds of America. I’m there to talk to scientists and interpretive specialists about the ways poetry can build a bridge between nature and culture. I fan lines of poetry and prose across a white tablecloth and ask each person to select something that excites them. Andre Copeland, the man who considers the solitary wolf spider his hero, selects a line by Scottish naturalist John Muir: When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.

Muir, who tied himself to the top of a fir tree in the Sierras to ride a windstorm, smell the chafing of resiny branches, and hear tense vibrations of pine needles against each other, reaches across 140 years to touch Andre Copeland—African American, Cherokee, inner-city Chicago kid, now head of interpretive programs at Chicago Zoological. Andre spins around, shaking his ribbon of prose, singing I got mine.

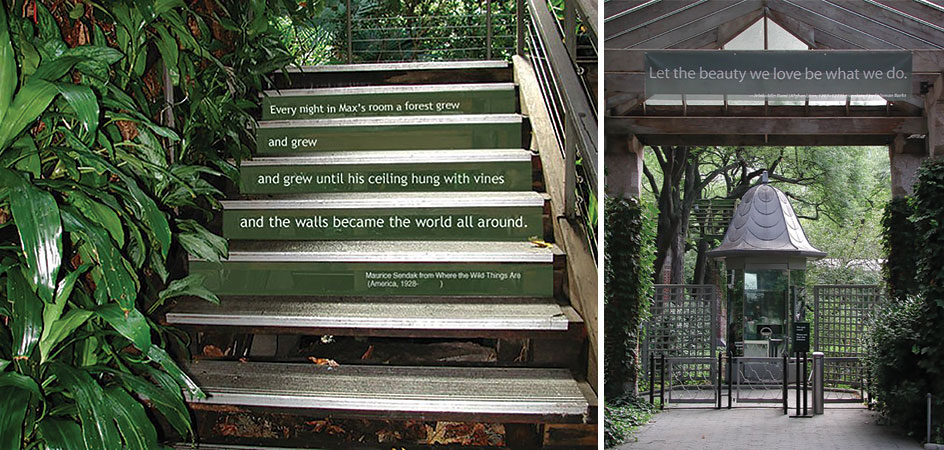

We will collaborate closely, and Andre will make certain the lines from Muir appear in the Great Bear Wilderness installation for the Brookfield Zoo. Additionally, he will carry our collaboration into the larger community, running poems across walls, up and down staircases of two local libraries, helping kids sow native grasses in gym shoes and senior citizens at a nursing home to caretake those grasses over the winter so that together seniors and kids will start a native garden in the spring.

I’m going home now, Andre’s mother had said to her young son as he lay in a hospital inside an oxygen tent. But I’ll be back. I want you to keep an eye on that spider while I’m gone. See how carefully it moves across the ceiling. By the time it crosses that ceiling two times, from that corner over there to back here, then back again, you just watch it, and by the time it has crossed that ceiling twice, I’ll be back beside you.

Because I have worked as a poet and activist in many environments, including a drug rehabilitation program at New York’s Lower Eastside Service Center; with nonviolent schizophrenics at the Post Graduate Center for Mental Health; and in Glacier, Yosemite, and Wrangell–St. Elias National Park, I knew this statement by conservation biologist George Schaller to be true: Any appeal for conservation must reach the heart, not just the mind. I designed a program called Poets in the Park for which all the schools surrounding Central Park used the park as a classroom. We studied geology not only by looking at the park’s bedrock and the small garnets found within but also by investigating the façades of surrounding brownstones, tenements, and office buildings. In 2004, while on academic sabbatical, I was invited by Poets House and the Wildlife Conservation Society to return to the city to serve as the poet in residence at Central Park Zoo, a jewel box zoological center designed by Kevin Roche, the architect of the Metropolitan Museum.

Central Park’s literary roots go deep. The park exists because of a poet, William Cullen Bryant. Frederick Law Olmsted, who believed public parks essential to the ideal of democracy, created it to be experienced like a poem, and many poets, including Federico García Lorca and Marianne Moore, spent hours sitting with animals inside the zoo.

The theoretical foundation of the Language of Conservation installation was left to me, and I decided, with one million visitors from all over the world reading these poems, I wanted the installation to be a celebration of our connection to the physical world and the poets selected to be those who worked in service to sustain that world.

Lyric poets like fifteenth-century Nezahualcoyotl, a ruler who planned cities, created zoological gardens and arboretums in pre-Columbian Mexico.

Could it be true we live on earth?

On earth forever?

Just one brief instant here.

Even the finest stones begin to split,

even gold is tarnished,

even precious bird-plumes

shrivel like a cough.

Just one brief instant here.

(trans. Edward Kissam & Michael Schmidt)

And Birago Diop, twentieth-century Senegalese poet, the former ambassador to Tunisia, who translated the tales of Wolof people and, as a veterinary surgeon, oversaw the building of an animal hospital in Dakar.

Listen more often to things than to beings.

Hear the fire’s voice.

Hear the voice of water.

Hear, in the wind, the sobbing of the trees.

It is the breath of the ancestors. (trans. Samuel Allen)

Judith Wright of Australia, considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature, was an outspoken supporter of aboriginal rights and environmental integrity. Her environmental poems, wrote a countryman, loved and studied now by generations of Australians, are today stopping more bulldozers than any environmental activists.

Egrets

Once as I traveled through a quiet evening,

I saw a pool, jet-black and mirror-still.

Beyond, the slender paperbarks stood crowding;

each on its own white image looked its fill,

and nothing moved but thirty egrets wading –

thirty egrets in a quiet evening.

Once in a lifetime, lovely past believing,

your lucky eyes may light on such a pool.

As though for many years I had been waiting,

I watched in silence, till my heart was full

of clear dark water, and white trees unmoving,

and, whiter yet, those thirty egrets wading.

For a special exhibit on amphibian conservation, I selected a poem by Abenaki poet Joseph Bruchac. With a background in poetry, publishing, and wildlife conservation, he has received national conservation achievement awards from the National Wildlife Federation. I was pleased to invite him to be part of our Language of Conservation team, which continues to grow in cities across the country.

Birdfoot’s Grandpa

The old man

must have stopped our car

two dozen times to climb out

and gather into his hands

the small toads blinded

by our lights and leaping

like live drops of rain.

The rain was falling,

a mist around his white hair,

and I kept saying,

“You can’t save them all,

accept it, get in,

we’ve got places to go.”

But, leathery hands full of wet brown life,

knee deep in the summer roadside grass,

he just smiled and said,

“They have places to go too.”

Language of Conservation collaborates not only with scientists and their interpretive staffs but also libraries, where we share the work of conservation writers and offer library programming that feathers beyond the libraries into schools, farmers’ markets, and even local banks.

Dr. Alejandro Grajal of Chicago Zoological speaks of the contemplative quality the installation of poetry brought to Great Bear Wilderness: People come here now for more than to fill their eyes; they come to fill their souls.

What do I believe this work can mean to the country?

When the poems went up in Central Park, the Wildlife Conservation Society discovered through exit interviews that a 48 percent improvement in the understanding of international conservation had taken place. Visitors arrived expecting the animals to entertain them and left asking how they could help sustain the life of the planet. We were contacted by readers from all over the world, from the environmental minister of Iceland, who wanted to know about W. H. Auden (unaware that Iceland was Auden’s iconic landscape), to a UN team planning Afghanistan’s first national park in Band-e Amir as well as wetlands restoration around the Kabul River.

At Chicago Zoological, our 7.5–acre installation is part of the Forest Preserve District. Great Bear Wilderness has partnered with the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, American Prairie Foundation, Vital Ground, and Polar Bears International, organizations that preserve hundreds of thousands of acres of critical habitat. The Mexican gray wolves, the most endangered wolves in North America, are part of the Great Bear Wilderness international recovery and reintroduction program. We continue to collaborate with members of the American Bison Society through three-nation conferences. Bison are one of nine iconic wildlife species that are recovering in 2019 due to global conservation action by the Wildlife Conservation Society. The other members of this group are tigers of western Thailand, humpback whales, jaguars, Burmese star tortoises, greater adjutant storks, Kihansi spray toads, maleos in Sulawesi, and Guatemala’s macaws.

Robert Hass said: Thoreau read Wordsworth, Muir read Thoreau, Teddy Roosevelt read Muir, and you got national parks. It took a century for this to happen, for artistic values to percolate down to where honoring the relation of people’s imagination to the land, or beauty, or to wild things was issued in legislation. . . . I think that the job of poetry, its political job, is to refresh the idea of justice, which is going dead in us all the time.

Poetry calls into question what it means to be human; it expands the imagination of a culture and suggests ways to become more humane and deeply engaged with the world.

San Diego State University