Proximate Pairings

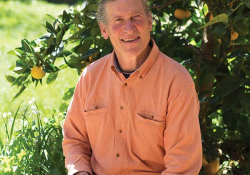

Vincent Segal & Ballaké Sissoko

Vincent Segal & Ballaké Sissoko

Musique de Nuit

Six Degrees

Now that a representative sample of the world’s recorded music is available at no greater cost than an hour’s worth of drill-down time on one’s favorite music streaming service, we have arrived at a time unprecedented in history where a musician with enough gumption can be influenced by everything, all at once. Moreover, musical recording technology has progressed to a place where any two musicians can creatively collaborate without even inhabiting the same physical space or, for that matter, speaking to each other.

Musique de Nuit, a collaboration between Malian kora player Ballaké Sissoko and French cellist Vincent Segal is both indicative of these global music forces and, pleasantly, a refutation of the disconnection that can emerge from communities of musicians no longer rooted in a particular geographic community.

The pair first collaborated in 2009 on Chamber Music to wide acclaim. What began as a successful experiment in collaborative composition has clearly evolved into something more vital, fueled by years of touring together. The result is Musique de Nuit, which was recorded in two sessions, one of which took place on the roof of Sissoko’s home in Mali.

The album is, with the exception of one song, a collection of duets. The kora and the cello are, on the surface, an odd pairing. The kora is a hybrid instrument that incorporates elements of the harp and the lute and, though its tuning can be altered, is fairly limited in its harmonic range. Sissoko is one of the world’s acknowledged masters of the instrument, and his command of rhythmic complexity, a staple of West African music, is breathtaking. Segal brings a full range of expressive techniques to the compositions, allowing him to suggest instruments in his cello lines that include other strings, percussion, and, in his most lyrical moments, even woodwinds.

The album opens with “Niandou,” featuring a quick shower of notes from Sissoko before the cello arrives to place the melody into a rhythmic context. Segal regularly changes up his parts within the song, thickening and diluting the rhythmic density to suit the intensity of the moment. Both musicians take short divergences away from the central melody, not unlike soloing in jazz, only to converge upon a unison line to punctuate the end of a section.

Segal’s sensitivity to West African rhythms is clearly on display in “Balazando” as he opens with a spasmic flurry of notes that might seem random (even accidental) in a European context but settle effortlessly into a polyrhythmic groove when Sissoko’s kora arrives in melodic support. The cello’s expressive range borders on supernatural under his fingers and bow on this song, with Segal drawing ghostly howls into the mix with subtle manipulations of his fingerings and attack.

The album’s longest track, “N’kapalema,” demonstrates the charms of this second collaboration as a whole. What begins with almost a chamber-music sensibility, an aching melody pulled along by notes as fragile as chandelier beads, slowly evolves into a complex web of frenetic rhythms that intersect in such a way as to never become cluttered. The resulting composition cannot be explained strictly within the context of Malian music, nor European music, but represents a genuine, collaborative mean that unites the best of both traditions while producing something wholly new.