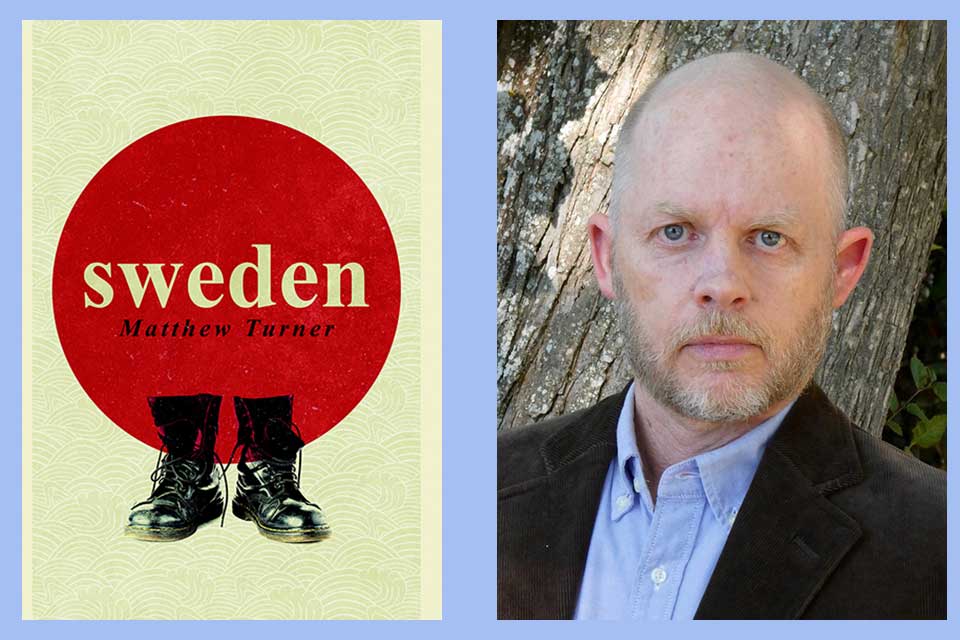

A Playlist for Sweden

Music—and jazz in particular—is an important element of Sweden, my debut novel about American deserters on the run in Vietnam War–era Japan. One of the three protagonists is an aspiring jazz trumpeter who works part-time at a record store in Tokyo. A number of the characters bond over their shared love of, or interest in, jazz. And music is crucial to many scenes. I’d like to introduce some of the songs that are either mentioned in Sweden or have some other close connection to the novel.

“September Song” – Sarah Vaughan with Clifford Brown

Described by AllMusic as “one of the most important jazz-meets-vocal sessions ever recorded,” Sarah Vaughan’s eponymous 1954 studio album of jazz standards was later reissued under the title Sarah Vaughan with Clifford Brown, reflecting the rise in stature of the young trumpeter affectionately known as “Brownie” who appears on eight of the album’s original tracks. As noted by Sweden’s Japanese protagonist, a young antiwar activist named Masuda, Brown never took drugs and drank only in moderation, distinguishing himself from many of his contemporaries whose careers and lives were ruined by substance abuse. It seems a cruel twist of fate, then, that Brown should have died so young, killed at the age of just twenty-five in an auto accident. A romantic and an idealist at the beginning of the novel, Masuda idolizes Brown as much for his clean living as for his trumpet playing. As a high school student, Masuda memorized Brown’s solos on two standout tracks from Sarah Vaughan with Clifford Brown, including “September Song,” composed in 1938 by Kurt Weill and Maxwell Anderson. Brown’s solo begins at 2:40.

“I Remember Clifford” – Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers

Continuing with the Clifford Brown theme, “I Remember Clifford” was written as a tribute to Brownie by jazz saxophonist Benny Golson. Originally recorded by Donald Byrd in 1957, the tune soon became a standard and was covered by many jazz musicians in the years that followed. This recording by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers is from a 1958 concert in Belgium featuring Lee Morgan on trumpet. I have chosen this version partly because it is the first version of this song I heard and partly because Art Blakey is also referenced in Sweden.

“One by One” – Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers

In chapter 22 of Sweden, James Earle Harper, an African American Marine who deserts while being treated at a US military hospital in Japan, meets Cleveland, a mysterious jazz-loving Black Muslim, in a bar in Yokohama’s Chinatown and is introduced to the music of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. The first tune Harper hears is “One by One,” the opening track to the 1963 live album Ugetsu. As Cleveland explains in the novel, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers first toured Japan in 1961, the experience leaving a lasting impression on Blakey and the members of his band. Three of the Jazz Messengers—Blakey, tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter, and trumpeter Lee Morgan—later married Japanese women. Ugetsu was recorded after the band’s second tour of Japan in 1963. Both the album’s title track, composed by the band’s pianist, Cedar Wilson, and “On the Ginza,” composed by Shorter, were included on the album as tributes to Japan. Shorter wrote three other tunes on the album, including “One by One.”

“I Got the Feelin’” – James Brown

Harper is not exactly impressed with Cleveland’s taste in music, explaining to the Black Muslim that he prefers “music you can dance to.” “What, you mean like Glenn Miller?” quips Cleveland. “Hell no,” retorts Harper. “I mean like James Brown.”

Interestingly, the relationship between Brown’s funk music and Blakey’s hard bop is closer than Harper and many others might imagine. As Wikipedia explains, “Brown’s band during this period [1967–70] employed musicians and arrangers who had come up through the jazz tradition. He was noted for his ability as a bandleader and songwriter to blend the simplicity and drive of R&B with the rhythmic complexity and precision of jazz.” “I Got the Feelin’” was released in 1968, the year in which most of the action in Sweden takes place, and reached number 1 on the R&B chart.

“Blue Rondo à la Turk” – The Dave Brubeck Quartet

In chapter 20 of Sweden, Masuda bonds with a young American deserter named Sullivan over their shared love of jazz music. Masuda hears Sullivan beating out a rhythm on an African drum and recognizes the distinctive combination of 9/8 time and standard swing time as the rhythm of Dave Brubeck’s “Blue Rondo à la Turk.” Brubeck composed the tune after hearing a group of street musicians in Turkey play a folk song in 9/8 time with subdivisions of 2+2+2+3. The tune appears on Time Out, a studio album recorded by the Dave Brubeck Quartet in 1959. The album title is a reference to the unusual time signatures of the tracks on the album. Time Out was considered risky by Brubeck’s recording company and received poor reviews on its release. However, it went on to become one of the biggest-selling jazz albums of all time, with one of the tracks, “Take Five,” becoming a top 40 hit single.

“We Shall Overcome” – Louis Armstrong

“We Shall Overcome” is referenced twice in Sweden. In chapter 29, Masuda and the other occupants of a car being pursued by police sing it to lift their spirits. Later, a version of the song is performed by a band in a New York City jazz club. I wanted to quote some of the lyrics to “We Shall Overcome” in the first of these two scenes. I assumed that because it was an old gospel number, the lyrics would be in the public domain. When I went to check this prior to publication, however, I was surprised to learn that the rights to the version of the song made popular during the Civil Rights era had been registered by Pete Seeger and were held by the Richmond Organization. I would have to gain permission to use the lyrics. Luckily, during the final editing phase of the novel, I learned that as part of a January 2018 settlement arising from a court case over rights to the song, TRO had agreed not to enforce any of the copyrights to “We Shall Overcome” that it claimed to own. I was therefore able to use the lyrics without having to gain permission. A number of jazz versions of this inspirational tune have been recorded over the years. Perhaps the most well known is this one made by the great Louis Armstrong.

“Dear Old Stockholm” – Stan Getz & Chet Baker

Sweden went through a number of title changes. It was originally called Ask Not What You Can Do for Your Country, which made perfect sense to me but few other people. Later, after being asked to change the title by my publisher, I looked to the titles and lyrics of jazz numbers and popular songs from the 1960s for inspiration. Early candidates included No Fortunate Sons, inspired by a line from the 1969 Creedence Clearwater Revival song “Fortunate Son,” and Their Foolish Hearts, inspired by the jazz standard “My Foolish Heart.” And for a short time, before it became Sweden, the novel was going to be titled Dear Old Stockholm. The song “Dear Old Stockholm” was made famous in the English-speaking world by the tenor saxophonist Stan Getz, whose own arrangement of the Swedish folk song first appeared on the 1951 album Vol. 2 by Stan Getz and Swedish All Stars featuring Bengt Hallberg. It was subsequently recorded by such jazz luminaries as Miles Davis, Paul Chambers, and John Coltrane. This recording is from a 1983 concert by the Stan Getz Quartet featuring Chet Baker (who is also mentioned in Sweden) on trumpet.

“Body and Soul” – Benny Goodman

In the novel, Masuda’s father was also once a jazz musician. Masuda senior performed in a big band before he was forced to give up his career when jazz was banned after the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941. Later, in the 1950s, he began collecting jazz records. One of his favorites (it sold out when it was released in Japan) was The Famous 1938 Carnegie Hall Jazz Concert, by Benny Goodman, a two-disc LP first released in the US in 1950. AllMusic describes the concert in question as “the single most important jazz or popular music concert in history” for its role in establishing jazz as “respectable” music.

Written in 1930 by Edward Heyman, Robert Sour, Frank Eyton, and Johnny Green, “Body and Soul” went on to become a jazz standard. While the 1939 recording by Coleman Hawkins is perhaps the definitive version of the song, younger readers may be more familiar with the Grammy Award–winning version recorded as a duet by Tony Bennett and Amy Winehouse in 2011, just months before Winehouse’s death.