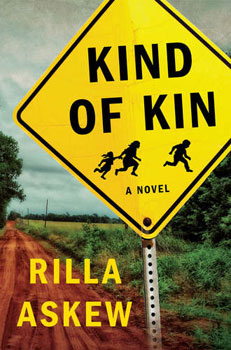

Kind of Kin by Rilla Askew

New York. Ecco / HarperCollins. 2013. ISBN 9780062198792

New York. Ecco / HarperCollins. 2013. ISBN 9780062198792

Rilla Askew’s fourth novel is a brilliant evocation of Heraclitus’s axiom that character is fate—an ironic evocation she both confirms and turns on its head. Askew’s characters are fated to have their strength continually tested in the face of narcissistic forces that would tear them apart as surely as any tornado, and in the end are stripped of all but their core integrity—thus remaining rich for us.

Georgia Brown Kirkendall, nicknamed “Sweet” from the 1920s jazz song “Sweet Georgia Brown,” is a masterpiece of narrative design as she faces challenges that would break most of us. Her husband, Tee, has turned in her father for harboring undocumented Mexicans, betraying Sweet even as she serves as the primary caregiver for Tee’s demented and incontinent step-grandfather. Sweet has raised her niece, Misty, whose deported husband just re-turned illegally, and is raising her ten-year-old nephew, Dustin, the other strong central character and first-person narrator. Dustin acts with courage beyond his years as he tries to help Luis—the sole illegal to escape the raid that captured Sweet’s father—find his sons in the Oklahoma Panhandle.

Askew contrasts the war between two kinds of religion, one self-righteous and judgmental, the other compassionate and fiercely risky, in a political crucible whose stringent anti-immigrant laws are tearing families apart. State representative Monica Moorehouse, author of the latest incarnation of immigration statutes, is driven by ambition, exploitation of fundamentalist fervor, and racial bias, which lead her toward loneliness and alcoholism even as her star rises politically.

Askew shows incomparable skill for illuminating the complicated and immediate context in which life-changing decisions are made. While Sweet is trying to keep Misty and her husband from the sheriff’s clutches in the church where she has claimed sanctuary for him, she also has to consider the fact that her grandniece, Lucha, needs food and diapers and is being traumatized by the situation without the capacity to understand what is happening. Sweet must negotiate basic problems such as a maxed-out credit card, no money for gas, and icy roads, all while trying to outwit a blustering, headline-hogging sheriff. Not only must she deal with a husband who wants to dominate her and yet is afraid of her superior moral power, she must also face the fact that her own son is a bully and a whiner, while her nephew, Dustin, son of her dead sister who was a drug addict, is much more like her—strong and loving. Askew’s message is grim, but far from noir or cynical. She manages deep suspense and deep character study with apparent effortlessness.

Askew immerses us in the frightening dynamics of every situation while illustrating the focused moral prescience of a novelist of superb acumen. Her Oklahomans prove that character is at once its own reward and its own punishment, and that the prosperity of moral treason is hollow.

Jim Drummond

Norman, Oklahoma